Improving Treatment Outcomes for People with OCD

By Helen Blair Simpson, M.D., Ph.D.

Helen Blair Simpson, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Psychiatry

Columbia University Irving Medical College (CUIMC)

Director, Center for Obsessive-Compulsive & Related Disorders

CUIMC & New York State Psychiatric Institute

President

Anxiety and Depression Association of America (2024–2025)

2010 BBRF Independent Investigator

2005 BBRF Young Investigator

WHAT IS OCD—AND HOW DO WE TREAT IT TODAY?

The hallmarks of OCD are in the name: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Its core features are obsessions, which are repetitive thoughts, images, or urges that a person finds intrusive and distressing; and compulsions, which are repetitive behaviors or mental acts.

These obsessions and compulsions are not simple one-minute problems. They are highly distressing, time-consuming, and impairing. I have patients with obsessive and compulsive behaviors that go on for hours, if not all day. And you can imagine that if you’re doing that, it can really interfere with your ability to function socially and emotionally, as well as with your family and at work.

While all patients with OCD have obsessions and compulsions, what makes one OCD patient different from another are what I call “associated features.” First, patients differ in the content of their obsessions and compulsions and their associated fears. In the field, we call these “symptom dimensions.” For example, one patient might have concerns about contamination, and intrusive thoughts about getting ill with a lot of washing compulsions. Another might have intrusive fears about harm befalling themselves or someone else with a lot of checking rituals. Other patients can be very concerned with symmetry and exactness and they’re trying to set things in order all day long. It isn’t that you can only have one type of symptom. Many patients have symptoms across multiple symptom dimensions OCD patients can also experience different affects. While many have intense anxiety and panic and can even have panic attacks, other OCD patients might have a sense that “it just doesn’t feel right” or even a strong sense of disgust.

Another thing that distinguishes OCD patients from each other is their varying degrees of insight about their condition. Some patients say, “I know that these washing rituals don’t make any sense. I know this is irrational, but I can’t stop,” but others really believe that if they don’t do that washing ritual, they might die. It’s also true that insight can vary over the course of the illness. A lot of times, kids with OCD may not know what’s real and what’s not real, and they might believe that their intrusive thoughts (such as that they can harm someone just by thinking) are real and it’s only with treatment or growing up that they realize it’s OCD.

It’s also important to note that while OCD can occur on its own, it often co-occurs with other disorders. In adults, the most common co-occurring disorders are other anxiety disorders or depressive disorders. Those with eating disorders also often have OCD. In kids, you can see a triad of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), tic disorders, and OCD. It’s important for people who are working with patients with schizophrenia to know that up to a quarter of patients with the illness will have OCD symptoms. All of this clinical heterogeneity sometimes can make it difficult for people to recognize and treat OCD.

The other thing I like to emphasize is how disabling OCD can be without treatment. Its affects 2% of the global population (about 160 million people). Half the cases start by age 19, and a quarter will start by age 14. Typically, when people start having symptoms and they meet the diagnostic criteria, the course of their OCD is chronic, with waxing and waning if not treated. Epidemiological studies show that if you have OCD, chances are you’re going to have moderate to serious symptoms. So, if you add this all up—the prevalence, the age of onset, the chronic course, and the moderate to severe symptoms— this is what makes OCD disabling.

TREATMENTS, AND HOW WE KNOW THEY WORK

The good news is we have two first- line treatments that we know work from clinical trials. One is a class of medications that we call serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), and they include clomipramine, which is an old-fashioned tricyclic antidepressant, but has very strong serotonin reuptake inhibition. And then we have clinical trials showing that selective SRIs such as fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram also work. [These medicines, widely prescribed for depression, are also known as SSRIs, and have trade names such as Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, Lexapro-- editor].

The other first-line treatment is a form of psychotherapy called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In OCD, we use a particular form called exposure and response or ritual prevention (EX/ RP). This is the therapy with the best evidence, and I’ll discuss it here in some detail.

First, what does a therapist do? They make a list with you of the types of situations or objects that trigger your OCD and ask you to rank how anxious or distressing these triggers are (rank them from 0 to 100). Then in a very focused and structured way, the therapist and patient collaboratively work to expose the patient to these triggers, going up the hierarchy of fears till they get to the top. During and after this exposure, the patient is trying not to perform their usual rituals. The goal of the therapy is to disconfirm the patient’s fears, to learn distress tolerance, and to break the habit of ritualizing. For example, if you have contamination concerns and don’t want to touch an ordinary item, for instance a trash can, disconfirming that might involve touching a trash can without ritualizing and realizing that a life-threatening illness does not follow. This is a way of challenging the distorted belief about the risk, developing distress tolerance, and breaking the habit of ritualizing and avoiding. The overall goal is to improve functioning and quality of life.

A well-studied standard format of EX/ RP is two sessions where you plan the treatment with your therapist, followed by 15 structured exposure sessions. We like to do it at least twice a week or more for a better outcome than just once weekly. A key part of this treatment is the daily homework, in which the therapist asks you to practice exposures in your home environment, to do your best to stop ritualizing, and to monitor your success. The therapist may also do home visits to promote generalization of the skills, because the goal is that the patient learns the skills and can use them in everyday life.

We know the effectiveness of this format from clinical trials, which are one major form of patient-oriented research. They test what treatments work.

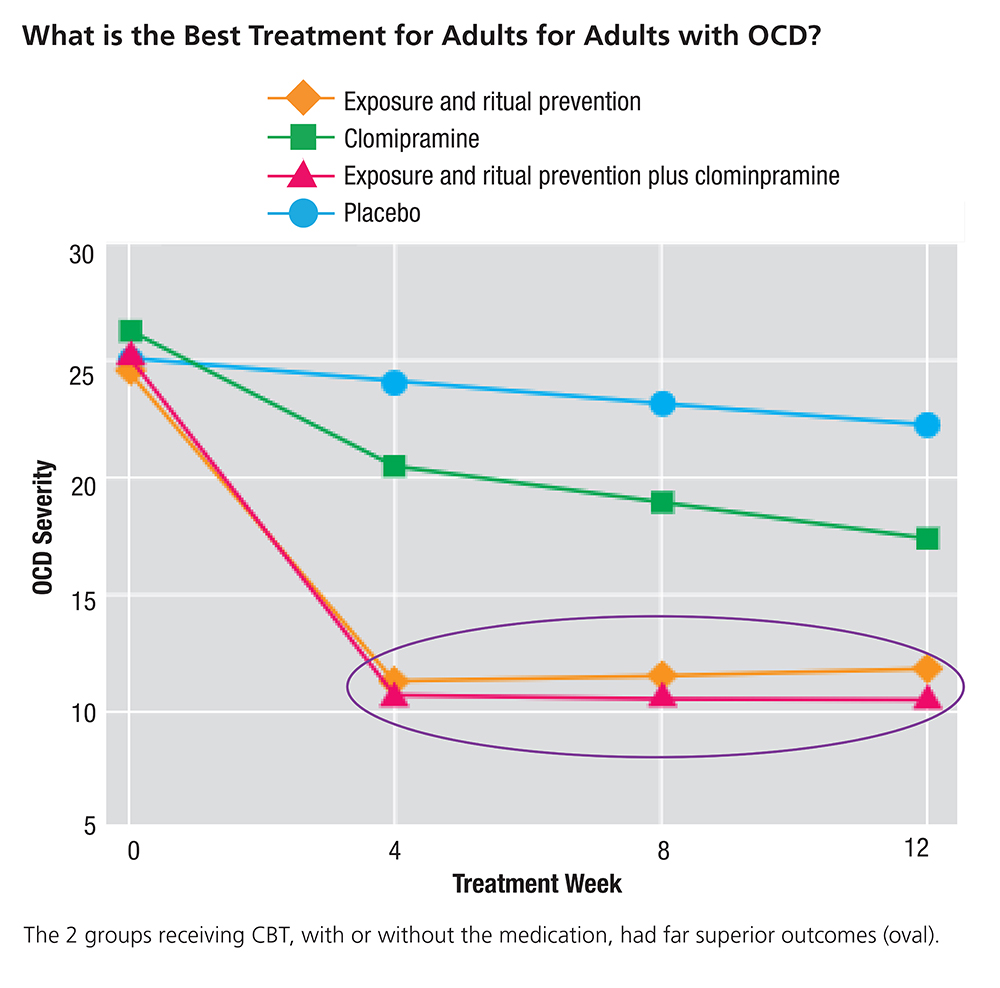

When I first came to Columbia University as a postdoctoral researcher, I was able to work on an important study led by Dr. Edna Foa, of the University of Pennsylvania, and Dr. Mike Liebowitz, who was my research mentor. The question they asked was simple: What’s the best treatment for OCD? In the study, they recruited 100 adults with OCD, and randomly assigned one group to a tricyclic antidepressant (the SRI medication clomipramine); a second group to receive CBT (the EX/RP form); a third group to receive a combination of the two; and a fourth group to receive placebo pill.

The group that received placebo over the 12 weeks of the trial had little change in symptoms. The group that was randomly assigned to the active SRI medication had a gradual decrease in symptoms over the 12 weeks. But the two groups that received the CBT, with or without the medication, had a higher and quicker decrease in symptoms than those taking the medication alone (see graph, below). This study really showed the power of CBT for the treatment of primary OCD. But back then, and still today, most people get medication first, mostly because it’s easier to take a pill than to commit to a course of in-person therapy.

Two subsequent clinical trials extended these results, in different ways. In one study, we asked if adding EX/RP to a stable dose of medication was better than accompanying SRI medication with a therapy that focused on teaching stress reduction and relaxation skills and did not specifically address the symptoms of OCD. This latter served as a control. We wanted to see if it was the specific skills learned by the patient in EX/RP that matter. The other possibility was that maybe all one needed for OCD to get better was meeting face-to-face with a caring, thoughtful therapist, i.e., there might be little or no extra benefit from doing EX/RP.

Another subsequent study, 5 years later, studied whether adding EX/RP to medication is better than adding an antipsychotic medication instead of an SRI. And why did we do that trial? Because in actual medical practice, that’s what psychiatrists typically did. If SRIs didn’t lead to enough symptom reduction—and most of the time, they don’t—psychiatrists would add an antipsychotic because clinical trials had shown that it worked.

WHAT THE TRIALS TAUGHT US

What we learned from both of these subsequent trials was that for OCD patients on SRIs who still have ongoing OCD symptoms, adding EX/RP to the SRI medication for adults with OCD was much better than adding the non- specific control therapy; and it was also better than adding an antipsychotic medication to SRI treatment. Across both studies, done years apart with completely different patients and different therapists, we found that about two-thirds of people who received EX/RP in addition to their SRI medication got better, and about one-third reported minimal symptoms after the trial. In a subsequent study we showed that if you went beyond the standard 17 sessions of EX/RP, increasing the number of sessions to 25, you could get two-thirds of people “well,” by which I mean having no or minimal symptoms.

What’s the take home message from not only this series of trials, but trials others have conducted? SRIs are effective for some, but response is usually partial. (In OCD, partial response is considered a good response). We don’t know why, but that’s the result. And what do we know from the clinical trials involving EX/RP? We learned that EX/RP is effective for more people than medication, but a key thing here is patient adherence. Patient adherence to EX/RP predicts outcome 6 months after the start of treatment, and, in particular, early adherence to the therapy can forecast how you’re going to do.

This means a therapist can have a good idea of how you’re going to do by the end of the second week of EX/RP therapy—just by knowing how quickly you start to adhere.

At the same time, from yet another clinical trial, we know that if you combine these two treatments (SRI medication and EX/RP), and optimize both, up to two-thirds of patients can attain minimal symptoms. That is a pretty incredible outcome for such a disabling disorder.

ALTERNATE TREATMENT SCENARIOS

But what if somebody, because of their symptoms, has a hard time doing the CBT treatment (i.e., EX/RP)? One strategy is to stop the treatment and focus in on the obstacles that are getting in the way. Are the exposures too hard? Is the ritual prevention or the demands too high? Can you tailor the treatment at the beginning to get the patient to see that it will work, but start a bit more gently?

One way to approach this is to focus on medication. Sometimes a patient’s symptoms are so severe that it’s really hard for them to focus on the therapy. By putting them on medication first— maybe even just for enough time for it to reduce symptoms to some degree— the patient may then be able to adhere to the EX/RP.

Another strategy is that of support and trying to make sure the patient has an environment, whether it’s the family or the work environment, that supports their adherence to the treatment. We also sometimes use more frequent sessions or even residential treatment, for a 24/7 therapeutic environment.

Having said that, I have seen people who don’t want to do EX/RP, and I believe patients should have choice, as long as they know it’s one of the most effective treatments we have. If they then choose not to do it, I honor that decision. What’s interesting is that I’ve had patients come back a year later, two years later, and say they’re now ready. This is often because SRIs, while usually well tolerated, can have side effects. It’s hard to take SRIs for the rest of your life. So sometimes, it’s about people, as they try to function in their lives, finding the motivation to take on EX/RP.

And this leads us to another question that patients ask us: If they’re on an SRI, and get the addition of EX/RP and they start feeling much better, can they then stop their SRI? What we discovered in the trial I mentioned earlier involving combining and optimizing treatments, is that on average, there is not a significant difference in symptoms of OCD or depression 6 months later between those who stayed on their SRI and those who were tapered off. However, after 6 months, 45% of those who tapered off were rated by their clinician (who did not know which group they were in) as clinically worse. Thus, if you are on SRIs for OCD and have minimal symptoms and are considering tapering off your medication, speak to your prescriber first and only taper off under close supervision.

These are the first-line treatment options for adults. Similar clinical trials have been done for kids, and the results similarly demonstrate the power of EX/ RP for the treatment of OCD in kids, as well as the typical partial response to medication, and that the combination of both is sometimes what works best.

THE IMPORTANCE OF EARLY DIAGNOSIS

As I noted earlier, half of OCD cases start by age 19 and a quarter of cases by age 14. So I’ve become a real proponent of early diagnosis and intervention, to prevent patients going through years and years of needless suffering.

Parents and teachers can and should look out for early signs in adolescents or even younger children. Avoidance is a pretty important sign. Sometimes in life it’s healthy to avoid difficult people or dangerous places. I’m not talking about that type of avoidance. But if you start seeing your kid not wanting to go to school or avoiding certain situations, that should be a red flag.

I’m a big believer that it’s better to get someone evaluated sooner rather than later because in the field of anxiety and OCD, we’re lucky. We have powerful psychotherapies that can help people. In fact, the first-line treatment for anxiety and OCD in young people is CBT. And frankly, they’re a skill set for life: to strategically expose yourself to what you fear and learn to master those fears. The more someone does this, the more resilience they build. Life has all sorts of disruptors for all of us, and skills learned from EX/RP can also help someone deal with the general ups and downs of life.

EX/RP is arguably the most effective treatment we have. And when you get the standard dose, which is 17 sessions, and it’s not enough, we increase the dose, giving people another eight sessions. Given the data we have, we really focus on enhancing patient adherence. Or if somebody is on a low dose of medication and is not experiencing side effects, we could increase the dose. For some people, that’s all they need to get a reduction in symptoms.

But sometimes, the first-line treatments (i.e., EX/RP and SRI medication) don’t work. Clinical trials are looking at second- line treatments in case patients don’t have a medication response at all or have a partial medication response. There are ongoing trials of ketamine, cannabinoids, anti- inflammatories, and psilocybin, among others. People are also studying how to improve EX/RP by increasing technology and access, enhancing learning, implementing intensive formats, as well as testing new therapies. And there’s a lot of work going on with transcranial magnetic stimulation, a non-invasive way of stimulating the brain to alter neural activity to reduce symptoms. All of the trials that are in progress are listed on clinicaltrials.gov. If you’re eligible, participating in these trials can be a great way to try something new while also helping to advance the science.

CONTINUING CHALLENGES

This leads me to two outstanding challenges in the field. The first is that most people with OCD don’t receive first- line treatments. And why is that? Sometimes the problem is that the patient doesn’t know they have OCD, so they don’t know how to ask for help. Further, in many parts of the world, stigma is a real issue and coming in for treatment is really hard. Even when a patient comes in, the clinician may not recognize the patient’s symptoms as OCD or may misdiagnose it or may not know the right dose of medication or the right therapy to deliver. Sometimes, the system of care doesn’t offer evidence- based treatment or insurance policies don’t cover those treatments.

To address this issue, we use a different type of patient- oriented research than clinical trials: we use “implementation science.” In implementation science studies, we figure out how to bring evidence-based care to real-world clinical practice. We are working to bring evidence-based care to New Yorkers through an initiative called IMPACT-OCD (https:// practiceinnovations.org/initiatives/impact-ocd/overview). This is a partnership between my Center for OCD and Related Disorders, the Center for Practice Intevention, and the New York State Office of Mental Health. If you are eager to learn more about OCD, there are public-facing resources there for both clinicians and families and those with lived experience.

Another challenge is that we have treatments that can help half of people. Why don’t our treatments work for most everyone? We don’t know yet. And that really leads to the fundamental question of what causes OCD. If we better understood the causes, we could perhaps understand why our treatments work for some but not all, and we could develop even better treatments.

What causes OCD? I think about this is two ways. First, what doctors call pathophysiology. How does the brain produce obsessions and compulsions? The working model we have is that specific brain circuits aren’t functioning properly. Frankly, that’s the working model we have for all psychiatric diseases. We know from a huge body of literature that there are neurocognitive and neurobehavioral alterations in people with OCD when you compare them to healthy volunteers. That can include alterations in how they process threat or extinguish fear. This can alter the balance between goal-directed and habitual behavior. It can impair their ability to inhibit responses or have cognitive control over their thoughts.

But pathophysiology is distinct from what we call etiology. Etiology is how did the brain develop those alterations in the first place? And that’s a different question. We know from past research that there is genetic risk for OCD, and we see this, in particular, in studies of identical twins. There also are cases of new-onset OCD after exposure to infectious agents, and there’s a hypothesis around autoimmune mechanisms. There have also been new- onset cases of people in their 50s or 60s after neurological insults and also after severe trauma. These suggest OCD in some cases may have an environmental cause. We also know from a huge body of brain imaging studies that there are alterations in multiple brain circuits in people with OCD.

But neuroimaging studies are a snapshot in time. Ideally, we want to know what’s the cause and what’s the effect? If you see an alteration in the brain, is it the symptoms causing the alteration or is the brain alteration causing the symptoms? And there’s another question I think about a lot. Do I think all of my OCD patients have exactly the same brain dysfunction? No. There’s some difference between patients in their clinical presentation, and I’ll bet at the end of the day when we really understand this, we’re going to see corresponding heterogeneity in the brain alterations involved in their symptoms.

A final thing to consider is whether neuroimaging findings are robust and reproducible. That’s a really important point because if you’re going to use a brain-imaging finding as a target for new treatment development, you want to know that you’re going to find that same target robustly and in a reproducible way. In own studies, we have sought to identify robust signatures in the brains of OCD patients. The idea of this research is to see if different brain alterations in different patients explain some of the different clinical presentations. Such information could help tailor treatments to different people for better outcomes. This is a move toward precision psychiatry.

As someone who’s been in the field of OCD research for over two decades, I’ve seen with my own eyes how research conducted in patients (including clinical trials, implementation science, and neuroimaging studies) has led to a better understanding of what causes OCD as well as to improved outcomes for OCD patients, and I see very exciting developments on the horizon. Thus, I ask all who are reading this: if you care about OCD and better treatments tomorrow than we have today, please join me in advocating for patient-oriented research. This is the research that can translate basic-science discoveries to clinical practice.

Click here to read the Brain & Behavior Magazine's January 2026 issue