Harnessing Potentially Therapeutic Properties of Psychedelics While Eliminating Hallucinations and Other Unwanted Effects

Considerable effort has been made in recent years to evaluate—or in some cases, reevaluate—psychedelic drugs for potential use as therapeutics to treat psychiatric disorders such as PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

None of this research so far has led to approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration of any “classical” psychedelic drug (such as LSD, psilocybin, or DMT) for any medical purpose, despite a number of clinical trials suggesting promise in specific applications and under specific conditions of administration. Among the lingering concerns are those relating to the hallucinogenic properties and abuse potential of these drugs, which continue to be listed by the U.S. government as prohibited Schedule I substances.

Even as clinical testing of psychedelics continues, these issues have inspired research on other tracks. In this article we will explore recent efforts by several BBRF grant recipients who are interested in some—but not all—of the properties of psychedelic drugs to treat psychiatric disorders. Our focus is on researchers who are not administering psychedelic compounds to patients, but instead are trying to isolate and capture some of their potentially therapeutic effects.

Some advocates of psychedelics in psychiatry have suggested that the “trip”—the subjective, perception- and consciousness-altering experience induced by these drugs—is an essential part of what makes them powerfully therapeutic. But this issue has not yet been addressed in a rigorous way by evidence-based scientific research. It’s a difficult thing to study, in part because the experience one has while under the influence of hallucinogens is not only subjective, but may even be uniquely personal.

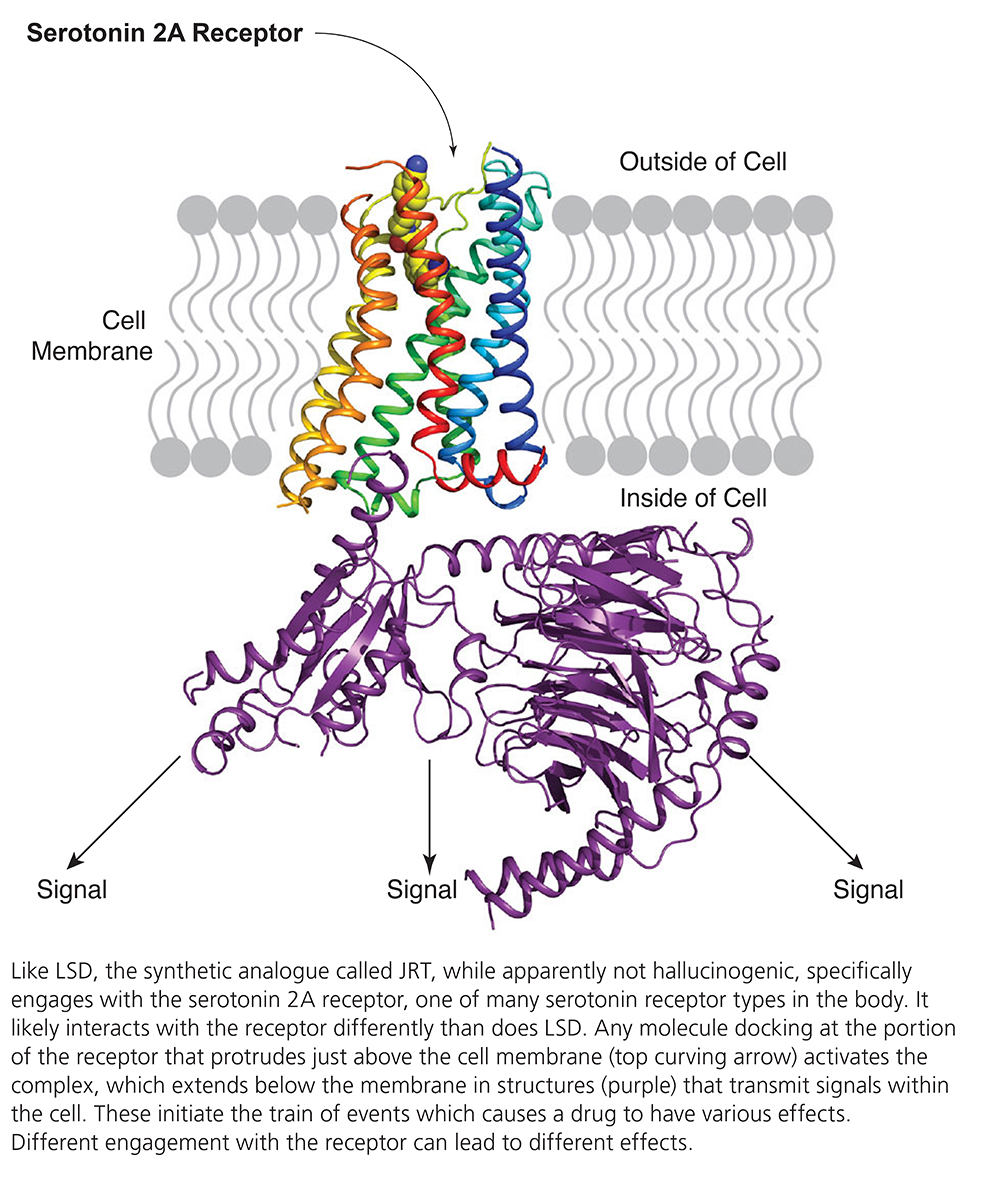

Past research has succeeded in establishing some basic facts about the complex pharmacology of psychedelics. Among other impacts, they are known to act upon the serotonin neurotransmitter system, which plays an important role in mood regulation.

Psilocybin, for instance, has been shown to stimulate several types of serotonin receptors in nerve cells, especially the serotonin 2A receptor. Such stimulation has a wide range of “downstream” pharmacologic effects in the brain and body, which remain poorly understood but could impact symptoms of mood disorders such as depression and anxiety. Animal studies have shown that MDMA, an amphetamine-based stimulant known on the street as “molly” and “escstacy,” which has a distinct mechanism of action, induces serotonin release by binding to serotonin transporter proteins. There is some evidence the drug may enhance the extinction of fear memories and modulate fear memory reconsolidation and thus it too holds promise in treating PTSD and anxiety.

As noted, it is not known whether or how the “psychedelic experience”— the subjective experience the user has after ingesting a psychedelic drug— may be related to therapeutic effects reported by users in the aftermath of the experience. But the experience of users varies widely. While some report life-altering insights or revelations while under the influence, others have described very difficult, emotionally painful, even harrowing experiences.

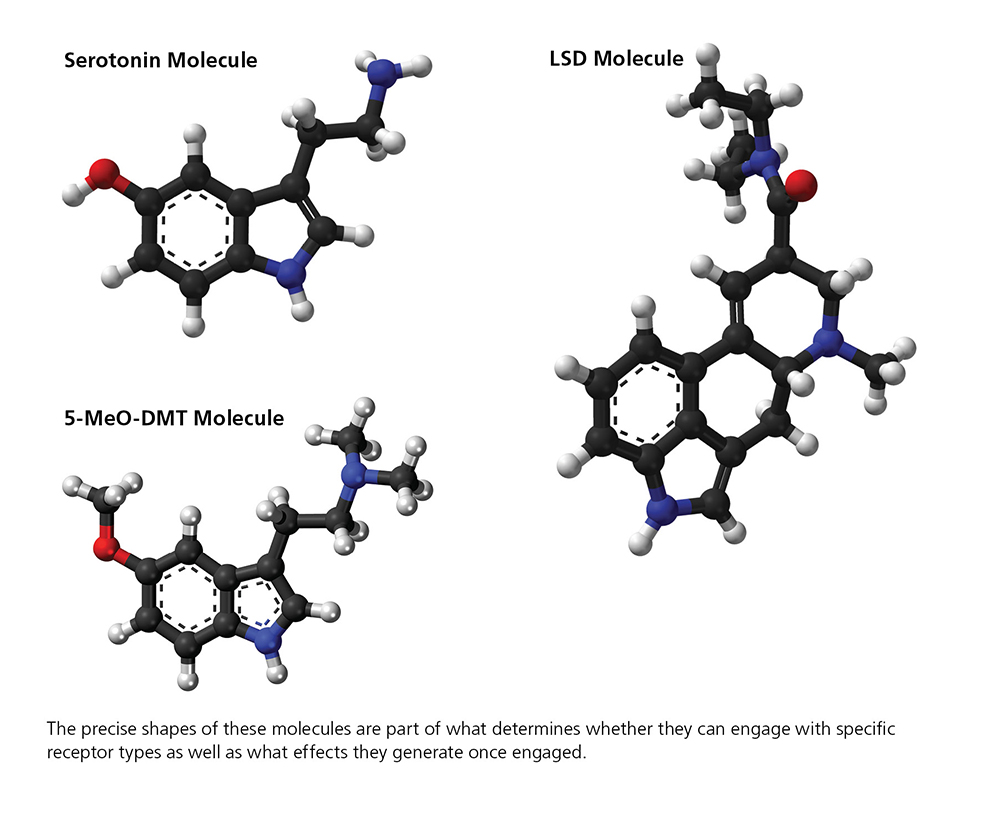

Alongside, but separate from what might be called applied research that explores how psychedelic compounds influence behavior in people, the disciplines of pharmacology, structural biology, and medicinal chemistry each and in combination provide pathways for learning more about the compounds themselves, their intrinsic properties which follow from their physical structure and interactions with other molecules as well as brain cells and circuits. These disciplines have provided the pathways taken by the grantees whose work we will now describe, which take four distinct approaches.

1. MODIFY THE MOLECULE’S STRUCTURE

For various reasons, the hallucinogenic properties of psychedelic drugs make these drugs particularly inappropriate and dangerous for people with schizophrenia and other disorders involving psychosis, which involve distortions of reality and difficulty distinguishing what is real and what is not.

But researchers also have recognized the power of some of these same substances to promote neuronal growth. Specifically, some psychedelic compounds have been shown to be powerful promoters of growth in atrophied cortical neurons, a fact that has intrigued researchers interested in addressing one of the hallmark pathologies associated with schizophrenia. Analysis of postmortem brains of people who suffered from the illness have revealed decreased branching of the dendrites that bring signals from other neurons into nerve cells in the cortex; reduced density of dendritic spines, the tiny bump- like protrusions along dendrites that are the points of contact for axons projected by neighboring neurons; and abnormally low levels of the proteins that form synapses in cortical tissue. All are manifestations of cortical atrophy.

It is inconceivable to contemplate treating schizophrenia with psychedelics, yet the problem of cortical atrophy has inspired some researchers to search for ways to modify psychedelics so as to retain their potentially therapeutic neuronal growth-promoting properties while reducing or eliminating their hallucinogenic ones.

In 2025, a team led by David E. Olson, Ph.D., at the Institute for Psychedelics and Neurotherapeutics at the University of California, Davis, reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) that they have modified the LSD molecule—a very powerful hallucinogen— to create a drug dubbed JRT. The new drug proved in a range of experiments to be “an exceptionally potent analogue of LSD,” yet with much lower hallucinogenic potential. The new drug appears to have “the ability to produce a wide range of therapeutic effects.” A powerful promoter of growth among cortical neurons, JRT also had strong antidepressant properties in animal tests and showed potential to address the negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia.

The research team included three BBRF grantees: William A. Carlezon Jr., Ph.D., a 2007 and 2005 BBRF Independent Investigator and 1999 Young Investigator; Conor Liston, M.D, Ph.D., a 2013 BBRF Young Investigator; and Alex S. Nord, Ph.D., a 2015 BBRF Young Investigator. Drs. Carlezon and Liston are members of the BBRF Scientific Council.

The researchers performed a remarkably simple modification of the LSD molecule, swapping the positions of just two atoms to create JRT. Like LSD, the new drug specifically spurs activity at serotonin 2A receptors. But the structural tweak that generated JRT also reduced its potential to generate hallucinations, as both test tube-based and mouse-based experiments indicated. “What I think is so interesting about this work is that JRT and LSD have essentially the same molecular shape and weight, yet they have distinct pharmacology thanks to the transposition of those two atoms,” Dr. Olsen says.

JRT proves to be a partial agonist, or stimulator, of the serotonin 2A receptor, as compared with LSD, which is a powerful agonist of the same receptor. This fact may explain JRT’s ability to promote cortical neuron growth with much lower hallucinogenic potential. In the team’s mouse experiments, JRT failed to cause behaviors that indicate hallucinogenic impact. In rodents, such behaviors include head-twitching behavior, hyperlocomotion, and deficits in prepulse inhibition, a measure of the brain’s ability to filter out irrelevant sensory information.

“Despite its lower hallucinogenic potential,” JRT in head-to-head comparisons with LSD and the antipsychotic clozapine “demonstrated superior effects on cortical neuron growth, [and] moreover produced a remarkable 46% increase in dendritic spine density” in living mice. Other experiments showed it “completely rescued cortical atrophy” in a particular layer of neurons in the mouse cortex.

“These changes in structural plasticity were accompanied by robust antidepressant-like properties and pro- cognitive effects,” in tests that included measuring active coping strategies in response to an unavoidable stressor. When mice were subjected to chronic “social-defeat” stress, the drug reversed anhedonia-like behaviors (inability to seek pleasure). JRT also “promoted cognitive flexibility” in mice performing a “reversal learning task,” a test in which an individual learns to abandon a previously learned behavior and adopt a new one.

The researchers believe their experiments highlight the potential of modifying the chemical structures of some psychedelics “to produce analogues with improved efficacy and safety profiles,” as in this case they appeared to have discovered a non-hallucinogenic stimulator of cortical plasticity and growth with potential to treat illnesses that cannot be addressed by psychedelics including schizophrenia, psychosis, and bipolar disorder with psychotic episodes.

The research on JRT continues. Dr. Olson, who is a co-founder and head of the scientific advisory board of Delix Therapeutics, the developer of the drug, continue to test it as a possible schizophrenia treatment.

2. ALTER THE MOLECULE TO TARGET A DIFFERENT RECEPTOR

It has been suggested that LSD, psilocybin, and other psychedelics called tryptamine hallucinogens exert both their hallucinogenic and therapeutic effects when they bind at the serotonin 2A receptor. But those and some other psychedelic compounds also engage with a variety of other receptors, including the serotonin 1A receptor. In such cases, what roles do the various receptor targets play in the drugs’ effects?

One psychedelic that engages both the 1A and 2A serotonin receptors is 5-MeO-DMT (sometimes called “five methoxy,” “bufo,” or “toad venom”), a toxin found in the glands of a toad found along the Colorado River. It’s very similar to the powerful psychedelic DMT (the active ingredient in ayahuasca), and like it and others, is being considered for possible use in certain psychiatric conditions. A small study conducted recently in Mexico with U.S. Special Forces Veterans tested 5-MeO-DMT in concert with the psychedelic ibogaine for relief of acute PTSD and depression. Both are Schedule I substances currently banned for human use in the U.S.

The type 1A serotonin receptor is a validated target of several FDA- approved drugs, including anti-anxiety and anti-depressant agents (buspirone and vilazodone). Yet, say a team of researchers led by Daniel Wacker, Ph.D., of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Dalibor Sames, Ph.D., of Columbia University, “little is known about how psychedelics engage it, and which of their effects are mediated by this receptor.” They recently published results of a study in which they and colleagues performed a detailed structural and functional exploration of the mechanisms through which several “classical” tryptamine psychedelics as well as 5-MeO-DMT and several prescription drugs bind to and activate the 1A serotonin receptor at the molecular and atomic levels. Scott J. Russo, Ph.D., a member of BBRF’s Scientific Council and a 2008 and 2006 BBRF Young Investigator, and Lyonna F. Parise, Ph.D., a 2022 BBRF Young Investigator, and were members of the research team.

In a mouse model of depression, they also tested a compound different but structurally analogous to 5-MeO-DMT that selectively targets the serotonin 1A receptor. One of the implicit questions they sought to shed light on was whether a drug targeting the 1A receptor alone, i.e., one that did not engage the 2A receptor, might still generate psychedelic effects, and whether it would still generate therapeutic effects (lowering anxiety and depression) ascribed to some psychedelics that bind primarily at the 2A receptor.

The team tested the 5-MeO-DMT analogue drug in mice subjected to social-defeat stress, which ordinarily leads the animals to avoid social interaction and to cease caring about seeking treats (similar to anhedonia in people). The analogue drug, which other experiments showed was a highly selective agonist of the serotonin type 1A receptor, “rescued” these deficits, the team reported, a finding with “potential implications for the therapeutic effects” of 5-MeO- class compounds in treating human psychiatric illnesses perhaps including depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Other parts of the study generated data supporting the idea that both the 1A and 2A serotonin receptors are involved in stress-coping mechanisms on both a psychological and cellular level; the role of the 1A receptor in stress resilience; and the previously reported antidepressant effect of drugs that specifically target the 1A receptor in animals.

There was also preliminary evidence that the 5-MeO-DMT analogue targeting the serotonin 1A receptor that was tested in mice “lacked the preclinical indications of classical psychedelic effects [e.g., the “head- twitch response”], which suggests that some of these compounds may not be hallucinogenic while retaining therapeutic effects.”

The team described how the configuration of tiny three-dimensional spaces within cellular receptors called subpockets—in this case, highly specific to type 1A vs. 2A serotonin receptors— ”determine both the potency and efficacy” of tryptamine hallucinogens at both receptors. This, they said, “provides a structure-guided framework that enables the development” of tryptamine psychedelic analogues “with finely tuned pharmacological activities and varying degrees of selectivity” for 1A and 2A serotonin receptor binding. Synthesizing and testing such compounds will be the subject of future studies.

Importantly, the team also suggested that FDA-approved medicines buspirone, vilazodone, and the antipsychotic aripiprazole, all of which target the serotonin type 1A receptor, engage with it differently than 5-MeO-DMT, generating signaling that is distinct from that produced when the psychedelic docks at the receptor to generate signaling outputs. These differences, as well as engagement of other receptor targets, probably accounts for the different effects of these medicines compared with the 5-MeO-DMT analogue tested in the socially defeated mice, the researchers said.

3. TARGET SPECIFIC CIRCUITS WITH NON-PSYCHEDELIC DRUGS

Another approach is to closely investigate the neural and circuit mechanisms though which psychedelics exert their effects. The hope is to see whether the brain cells and circuits that drive hallucinogenic effects are perhaps distinct from those that drive specific therapeutic effects.

New research of this kind, reported in 2024 in the journal Science, was led by 2021 BBRF Young Investigator Christina K. Kim, Ph.D., a UC Davis collaborator of Dr. Olson, mentioned earlier. A co-author of the new paper, Dr. Olson said the idea of decoupling putative beneficial effects of psychedelics from their hallucinogenic effects is not, in this research, “a matter of chemical compound design,” as it is in Method 1, described on pages 31–33. “Rather, it’s a matter of targeting neural circuity.”

Drs. Kim, Olson and colleagues used a sophisticated technology in mice to apply genetics-based tags to neurons in the brain’s medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). This is an area where psychedelics engage the serotonin system, generating powerful “plasticity” effects. The psychedelic drug the team administered to their mouse-subjects is called DOI, a well-studied compound that targets, as many other psychedelics do, the serotonin 2A receptor.

In the minutes immediately following DOI administration, while mice were experiencing hallucinogenic effects (evident in their head-twitching behavior), the team used a technology called scFLARE2 to tag neurons in the mPFC that had been activated by the drug. These tags could be “placed” in the very short time window in which the drug is most active—a matter of minutes.

The tags enabled the researchers to molecularly profile the activated neurons, and also, in subsequent experiments, to selectively manipulate their firing using optogenetics, a technology co-developed by BBRF Scientific Council member Karl Deisseroth, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues that renders specific neurons sensitive to activation with laser light of a specific color.

The experiments revealed a psychedelic- responsive network of neurons in the mouse mPFC that included many neurons expressing the serotonin 2A receptor, but, importantly, not only these cells; the network extended beyond the population of cells bearing the receptor. This was a crucial discovery that helped the team determine that the hallucinogenic effects of the drug and capacity to reduce anxiety-like behaviors are not inextricably bound together but may in fact be distinct, in terms of neural circuity.

Long after the hallucinogenic effects of DOI administration had ended in the mouse-subjects, the team found it was possible to use optogenetics to reactivate the neural network initially activated by the drug and associated with anti-anxiety effects, and in so doing, restore the anxiety-reducing effect of the drug when it was originally administered. This reactivation of tagged neurons, in fact, took place a full day after the drug had been administered and had long cleared the body.

“We thought that if we could identify which neurons activated by DOI were responsible for reducing anxiety, then we might be able to reactivate them at a later time to mimic those anti-anxiety- like effects,” Dr. Kim says.

The team noted that while DOI is a potent psychedelic, it is not being considered as a potential therapeutic in the clinic. The point of the study was to dissect the basic circuit mechanisms that enable one psychedelic to exert both hallucinogenic but also anti- anxiety effects. Discovering circuity that specifically mediates the anti- anxiety effect in the case of DOI may be possible to extend to studies of other drugs and other impacts—for example, the anti-depressive or fear-extinguishing impact that some psychedelics have been reported to have in clinical tests. These potentially could reveal circuitry that might be specifically targeted in future therapies.

4. DISTINGUISH HOW PSYCHEDELCIS INTERACT WITH DIFFERENT NEUROTRANSMITTER SYSTEMS

For several years, Robert C. Malenka, M.D., Ph.D., a BBRF Scientific Council member and a 3-time BBRF grantee and prizewinner, along with some of his Stanford University colleagues, have been pursuing what they call a “circuits-first approach” to research aimed at better understanding psychedelic and other consciousness- altering drugs and their potential to be useful in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses. They have urged that by using modern neuroscience tools to “define the [brain-]circuit adaptations that contribute to a drug’s behavioral and therapeutic effects, studies can be conducted to reveal new molecular targets in brain cells or circuits” which might be used as a basis for developing novel versions of psychedelic drugs that have maximum therapeutic impact and cause fewer side effects.

In a paper published this past July in Molecular Psychiatry, Dr. Malenka, along with senior collaborator Boris D. Heifets, M.D., Ph.D., and a team that included 2023 and 2020 BBRF Young Investigator Neir Eshel M.D., Ph.D., show some of the fruits of the “circuits- first” approach. They closely studied how the drug MDMA exerts its principal effects—some undesirable, some potentially therapeutic—and found separate mechanisms that appear to be responsible for each. Taken together, the results suggest how and why MDMA appears to have lower abuse potential than some other psychotropic drugs, and may have potential for use as an “enactogen,” a drug that induces feelings of empathy and emotional openness.

MDMA is not a “classical psychedelic,” although it can have weak psychedelic effects. The behavioral effects of MDMA in assisted therapy applications tested in small trials in people with PTSD have indicated its characteristic properties: an enhanced sense of emotional connectedness and empathy, along with reduced fear when confronted with aversive stimuli like traumatic memories. But MDMA, an amphetamine, is prone to misuse and abuse, which, the team notes, is “an important risk consideration for treating patients with PTSD, many of whom have comorbid substance use disorders.”

At the same time, MDMA is not as widely abused as closely related amphetamine drugs, such as methamphetamine. The question the researchers explored was whether MDMA’s reduced abuse potential is mechanistically linked to its therapeutic behavioral effects. Prior work by the team indicated that MDMA has a molecular affinity for the protein that transports dopamine molecules in the brain, called the dopamine transporter (DAT). Like all amphetamines, MDMA amplifies dopamine release in the brain, which generates an intensely rewarding feeling—and is also the reason it can be addictive.

But unlike meth, MDMA also has a high affinity for the protein that transports serotonin in the brain, called the serotonin transporter (SERT), the new research indicated. In a major reward center of the brain called the nucleus accumbens (NAc), serotonin release appeared to account for MDMA’s prosocial effects in various mouse experiments. This prosocial effect was the result of an interaction between MDMA and SERT, and subsequent activation of one of the many receptors for serotonin in the brain—the serotonin 1B receptor, in cells in the NAc.

In contrast, the nonsocial drug reward evoked by meth—as well as high doses of MDMA—appear to be traceable to dopamine release, in the same brain structure, the NAc. This raises the question of whether and how the specific dopamine- and serotonin-enhancing effects of MDMA in the NAc might be mechanistically related.

The form of MDMA administered in the experiments at various dosages (from low to high), called R-MDMA, is a version with a structural configuration that gives it distinct properties compared to conventional MDMA. Multiple structural forms of MDMA were administered for comparison purposes, as well as methamphetamine and cocaine. Tests were performed revealing the addictive properties of the drugs based on conditioned expectation of reward, as well as tests in which the social behavior of the animals could be closely observed before and after drug administration, including in animals with transporters for serotonin or dopamine genetically deleted.

One finding was that serotonin released after R-MDMA administration had the effect of limiting the release of dopamine, via activity observed in the NAc.

Further experiments revealed that R-MDMA’s activation of a specific receptor for serotonin in the NAc—the serotonin 2C receptor—actively suppressed dopamine release in that brain structure. This action, the team suggested, may account for MDMA’s lower addictive potential.

Other experiments provided evidence for the possible source of MDMA’s prosocial effects. The form being tested as a potential therapeutic, R-MDMA, appears to have prosocial effects because it is more active at serotonin transporter molecules (SERTs) than at transporters for dopamine (DATs), especially in comparison with the standard form of MDMA, which affects these transporter molecules more evenly.

Importantly, the precise cellular location of the serotonin 2-C receptors in the NAc linked with the drug’s limitation of dopamine release and thus its lower abuse potential is still unclear, and should be taken up in subsequent research, the team said.

Results of their study provide, they said, reason to continue exploring the use of R-MDMA (at low doses) in the clinic for therapeutic purposes in patients with illnesses like PTSD that often do not respond satisfactorily, or over the long-term, to current treatments.

Written By Peter Tarr, Ph.D.

Click here to read the Brain & Behavior Magazine's January 2026 issue