How the Search for Genes Involved in Mental Illness Has Led to Key Insights About Reducing Medication Side Effects

James L. Kennedy, M.D.

Scientific Director, Molecular Science

Head, Tanenbaum Centre for Pharmacogenetics

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health

University of Toronto

BBRF Scientific Council

2013 BBRF Distinguished Investigator

1995 BBRF Independent Investigator

1990, 1989, 1988 BBRF Young Investigator

By Peter Tarr, Ph.D.

People who are ill and those who love and care for them want medicines that work. This yearning provides a powerful fuel for researchers and clinicians the world over. Among them is James L. Kennedy, M.D., a distinguished professor at the University of Toronto and its affiliated Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). Dr. Kennedy is one of only two people with the distinction of having been awarded five BBRF grants (the other is Flora Vaccarino, M.D., a pioneering neuroscientist in brain development at Yale University).

Dr. Kennedy, who, since 1996, has been a member of BBRF’s Scientific Council, is keenly aware of the need for new and improved treatments. He was trained in clinical psychiatry and still treats patients, with a current focus on aging patients with schizophrenia. His attention to patients, and his personal connection to their problems and unfulfilled needs, provides a key link to the research activities to which he has devoted much of his professional life.

Dr. Kennedy has helped to build the scientific foundation for a field called pharmacogenetics. Its aim is to figure out how to optimally match individual patients with specific therapeutic medicines. Pharmacogenetics does this, as the name implies, by harvesting knowledge about the human genome—specifically, the individual DNA variations that each of us has—and connecting it with biological understanding about how drugs are metabolized by the body, and how individual genetic variations make some of us very good or rather poor candidates for specific medicines. In recent years, the same idea that has animated pharmacogenetics has been popularized in the idea of “precision medicine.”

To paraphrase Dr. Kennedy, referring to the possibility of each of us knowing which drugs are most and least likely to help us: “Who wouldn’t want to know that?!” Remarkably, the field that his research helped to establish has already made this a possibility for a large number of people with psychiatric illnesses—as many as two-thirds of those taking medicines for schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder and other conditions. The opportunity presented by pharmacogenetics is the subject of the accompanying story. In this story, we explore the career of Dr. Kennedy, focusing on the way in which his treatment of patients informed and encouraged his research activities, which began with a broad effort “to identify genes involved in mental illness.” In this journey, in which BBRF has played an important part, one of the highlights, described here, was a genetics discovery that led to a new medicine for a motor disorder that has helped many thousands of people, including some who take antipsychotic medicines for schizophrenia.

QUESTIONS WITH NO ANSWERS

Like many people who go on to careers in psychiatry and psychology, Dr. Kennedy, “a boy from a village of 200 people in rural Ontario,” was fascinated at any early age with “a bunch of questions about human nature,” questions which seemed to have “no satisfactory answers.” As an undergrad he learned as much as he could about psychology and the biology of the brain (as it was understood at that time). For his master’s degree, he had his first experience with research, working on a project exploring the biology behind the harmful behavioral impacts in children caused by exposure to lead. Wanting to continue with research, specifically in psychiatric disorders, he attended medical school at the University of Calgary, which offered such opportunities, and he led a project that in 1986 resulted in the first of Dr. Kennedy’s published papers in psychiatry (there are now over 900). It showed how certain instinctual behaviors, including dominance displays and scapegoating, could impair group psychotherapy.

By the time Dr. Kennedy went to Yale University for his residency in psychiatry, in the mid-1980s, 30 years had passed since James Watson and Francis Crick first described the elegant double-helical structure of DNA, the genetic material. In this long intervening period, brilliant, difficult, and meticulous research had revealed how genetic information is copied and translated into the myriad proteins that give cells and bodily organs their structure and enable them to perform highly specific functions. Insights afforded by genetics research were naturally also applied to human illness, and to processes in the body that go awry because of genetic mutations. But this was a difficult task a full decade before rapidly advancing technologies were brought to bear upon the grand-challenge task of sequencing, i.e., “spelling out,” the full human genome, work that was not completed until after the year 2000.

In psychiatry, an era of “biological psychiatry” was blossoming, with an explosion of interest in studying underlying biological processes in the brain that might help explain the behavioral patterns long associated with specific illnesses. Dr. Kennedy was right in the middle of the action, involving himself in research at Yale on the genetics of schizophrenia—even as he performed his work as a clinician, treating patients with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

This was right around the time that BBRF and its Scientific Council were formed by a group led by the late Herbert Pardes, M.D. Then called NARSAD (the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression), the organization in 1987 had just awarded its first 10 grants. Early the following year, Dr. Kennedy applied for what would be the second round of BBRF grants. “I had a project on the genetics of schizophrenia, using a very large pedigree,” he remembers. His project proposal bore the provocative title, “Is There a Gene for Schizophrenia?”

Knowing what we know today, it is easy to dismiss the idea that a single gene would account, by itself, for the many and varied symptoms of the illness, and even less probably, in every patient. But it was definitely a question worth asking: it had recently been discovered that mutations in a single location (“locus”) of the genome on chromosome 4, and perhaps a single gene within that location, was responsible for the pathology that generated Huntington’s Disease, which, like schizophrenia, has a diversity of symptoms. The techniques making the discovery of the Huntington’s gene possible were ingenious and painstaking; it had taken years to find the genetic culprit. In addition to advances in technology, the discovery was possible because Huntington’s researchers had access to a large and unique group of patients from the same family with the illness—a “large pedigree.”

TRANSFORMATIONAL FIRST GRANTS

Dr. Kennedy’s 1988 bid for a first BBRF grant involved exploring whether a similar strategy might reveal “a gene for schizophrenia.” The young researcher was awarded the grant by the fledgling Foundation, and, as he tells the story, it had a “transformational” impact on his career. Modestly, he says that without the grant he would have “fallen upon the rocks, I would have struggled.” His subsequent success gives us reason to doubt this. But it is certainly true that, as he puts it, this early-career vote of confidence from BBRF was what enabled his career to “explode.”

During the year of that first grant (BBRF grants were then funded for a single year; today, Young Investigators receive 2 years of support) Dr. Kennedy was the lead author of a paper appearing in the prestigious scientific journal Nature. The paper was about well-documented efforts to link DNA “markers” on chromosome 5 with schizophrenia. The techniques used in making this linkage were of the same type used in the Huntington’s gene research. In their paper, Dr. Kennedy and colleagues expressed optimism about the value of the method, but made the important point that results in the large cohort of Swedish patients showing a schizophrenia linkage on chromosome 5 were not replicated in similar studies using different patient cohorts.

Presciently, given the state of the science at that point, Dr. Kennedy and colleagues ventured that additional research would ultimately show that “the genetic factors underlying schizophrenia are heterogeneous,” i.e., not limited to a single location on a single chromosome. In other words, they were suggesting that, unlike in Huntington’s, a “single gene” for schizophrenia would most likely not materialize. (Today, using much more sophisticated technologies and with full knowledge of the human genome sequence, several hundred genome variations have been associated with risk for schizophrenia: see illustration, below.)

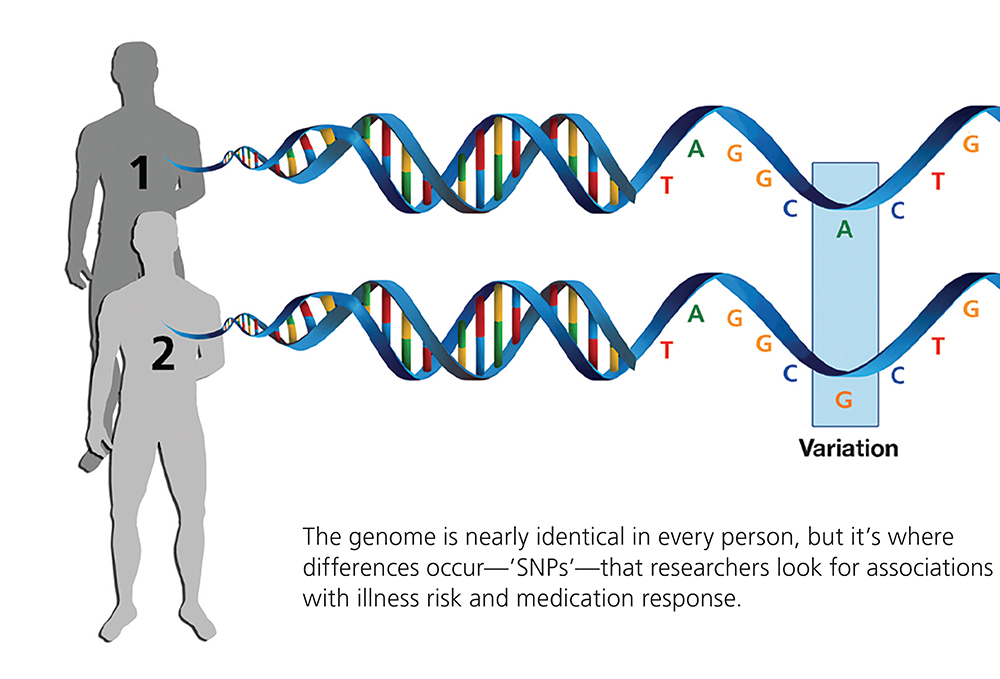

Two additional Young Investigator grants were secured by Dr. Kennedy in the subsequent 2 years, as he began to follow up on this notion of “genetic heterogeneity” in schizophrenia. Some of the work sought to identify single- nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs (pronounced “snips”)—single DNA “letters” among the 3 billion pairs of letters comprising the human genome (each letter standing for one of the four chemical DNA “bases”) that vary between individuals. In some genome locations, single DNA letters differ in people with schizophrenia compared with people without the illness. The hypothesis was that these DNA variations in patients were in some way related to elevated risk for the illness.

Research would eventually show that there are millions of SNPs in the human genome, and each of our genomes is studded with them. Most SNPs, it turns out, are part of normal genetic variation and have no effect whatever on our health. But in the context of serious illness, the critical question initially was: do certain SNPs occur consistently, or with above-average frequency, in significant numbers of patients with specific illnesses?

If so, were these DNA variations related to biological factors that helped cause the illness or raised the risk of having it? Perhaps the illness-related variations in schizophrenia patients in some way impaired the function of genes essential in prenatal brain development or postnatal brain function. These questions are still in play, although the consensus is that most illness-linked SNPs, considered alone, raise illness risk (in schizophrenia and other common disorders) by a tiny amount. It is thought that having multiple illness-associated SNPs, or particular constellations of them, in some cases in concert with specific environmental factors, is what can alter biology and raise the risk that a particular individual will develop the illness.

Other kinds of genetic variations— deletions or multiplications of certain DNA sequences, for example, or deletion or rearrangement of a part of a chromosome—can have catastrophic biological impacts and by themselves cause an illness like schizophrenia. These insights were still years away in 1990 when Dr. Kennedy received his third BBRF grant, to study the “molecular genetics of schizophrenia.”

In retrospect, we can say that he was among the generation of researchers who, in Dr. Kennedy’s words, “had the right skills at the right time” to forge the research path and step by step make the key discoveries that have since revealed much (but far from all) about the association of schizophrenia and other illnesses to genetic variations.

RELATING VARIATIONS TO MEDICATION SIDE EFFECTS

One near-term impact of having received three early-career BBRF grants was that Dr. Kennedy found himself in considerable demand. In 1991, he moved to the University of Toronto, where “a great genetics lab had been established.” Genetics research on schizophrenia was moving away from large-pedigree family studies to studies analyzing patterns of genetic variation in large numbers of people with the illness—people who were unrelated— and comparing them with large numbers of people without the illness (“controls”). These were precursors of what became the standard tool for such investigation, called genome-wide association studies (GWAS), which sought to find statistically significant correlations between individual SNPs and illness risk.

While these seminal developments in genetics were under way, Dr. Kennedy at the same time was establishing a clinical practice at Toronto focusing on treating people with schizophrenia. This would have a crucial impact on his genetics research.

While treating patients, he remembers, “it hit me how inaccurate, imprecise— we could even say clumsy and blunt— our antipsychotic medications were.” It so happened that a colleague at the University of Toronto had established a clinic specifically to investigate tardive dyskinesia (TD), a disorder that involves involuntary repetitive movements affecting the face, mouth, or other parts of the body. TD was among the more serious side effects of first- generation antipsychotic medicines, and one that Dr. Kennedy had begun to study from a genetics perspective. Might there be variations in specific human genes that predispose certain individuals to develop TD? “I was very focused on that, as well as the much more complicated question of predicting who would and would not respond to antipsychotic medicines.”

In a good illustration of how BBRF has made a tangible impact on the course of brain and behavior research, Dr. Kennedy’s connections with the Foundation, already strong after receiving three grants, “put me in touch with Dr. Herbert Meltzer, who headed the Young Investigator grant program for many years.” Dr. Meltzer, who, like Dr. Kennedy, was among those who received grants in the Foundation’s second year of existence, was in close touch with those then conducting clinical trials of clozapine. That drug would become the first of the “second generation” of antipsychotic medicines to be approved by the FDA. Dr. Meltzer went on to perform research demonstrating clozapine’s great value in reducing suicide risk in schizophrenia patients.

Most medicines have side effects. Clozapine proved highly effective in reducing hallucinations and delusions in schizophrenia (it did this as well and often better than first-generation antipsychotics, especially in treatment- resistant patients). But, it proved to be linked with side effects of its own, including significant weight gain followed by diabetes in some patients.

Dr. Meltzer and others sent blood samples and information from the clozapine clinical trials to Dr. Kennedy, who was able to extract DNA and study possible genetic factors related to the weight-gain side effect of this new class of antipsychotics, adding it to his ongoing study of the tardive dyskinesia side effect from first- generation medications. In parallel with these side-effect investigations, he continued to work on the question of who would and would not respond to these medicines, or, to put it differently, the problem of treatment resistance in schizophrenia.

In the 2000s, with the advent of the powerful GWAS approach, Dr. Kennedy and Dr. Anil Malhotra, a more recent BBRF grantee (now, as is Dr. Meltzer, a BBRF Scientific Council member) performed important studies that led to the discovery of variations in a gene called MCR4 which was linked with weight gain in schizophrenia patients taking clozapine or olanzapine, both second-generation antipsychotics.

“It was thrilling, absolutely thrilling!” Dr. Kennedy well remembers, referring to his presentation with Dr. Malhotra of this result to colleagues in 2012. Soon thereafter, further probing by Dr. Kennedy enabled him to flag another gene responsible for encoding three proteins that had a direct impact on weight-gain risk. That gene, he notes in passing, is called GLP-1—the gene that encodes a receptor that is the target of diabetes and weight-loss drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy that have made so much news in recent years.

‘FROM GENE TO TREATMENT’

In the meantime, other research was beginning to shed new light on the original side-effects question pursued by Dr. Kennedy, that of a possible genetic factor disposing some who took antipsychotics to tardive dyskinesia. In the early 2000s, another early BBRF grantee who would join the Scientific Council, Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman of Columbia University, led a team that performed the largest- ever randomized clinical trial of antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients. That study found that while all the tested antipsychotics were effective for treating the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (hallucinations and delusions), individual differences in side effects and tolerability led to high discontinuation rates. Following these important initial findings, an investigation of the DNA samples from the trial participants suggested the possible importance of several genes—including ones in the dopamine neurotransmitter system—that appeared to impact side-effect risk.

This preliminary finding became important to Dr. Kennedy some years later, when he led “a very precise, precision-medicine study” with a cohort of schizophrenia patients that he and colleagues had been following in Toronto. “At that time, we probably had the world’s largest sample, based on our clinic here, that was well characterized over time. We’d been collecting patients with the tardive dyskinesia side effect for 15 years at that point.” This story illustrates how basic research and clinical research can come together to generate a finding of great import that could not have been anticipated in advance. “In 2013, we published a paper pointing to a key gene, out of all the dopamine system genes, that was predictive of risk for the tardive dyskinesia side effect in antipsychotics.” It was a gene called VMAT2 that encodes a transporter protein that takes free- floating dopamine inside a cell and puts it into tiny balloon-like structures called storage vesicles.

Two variants of the gene were examined. One version increased the amount of the VMAT transporter protein in the brain and the other variant decreased it. In 2013, Dr. Kennedy’s team, in research led by Dr. Clement Zai and directly supported by his BBRF Young Investigator grant in 2012, published a paper stating that it was the version of the VMAT2 gene which caused an excess of the transporter protein in neurons that created a high risk for the tardive dyskinesia antipsychotic side effect.

The story has a remarkable coda—an unexpected major payoff.

“We had said that VMAT2 would be an important target for developing treatments for tardive dyskinesia, for which at that time there were no treatments at all,” Dr. Kennedy remembers. “We said, further, that an excess of the transporter protein was the mechanism of risk, so it would make sense to try to develop an antagonist”— something that would reduce the excess.

A California company called Neurocrine Biosciences had been developing a candidate drug called valbenazine that targeted the VMAT2 protein. They had been hoping to use it to treat Huntington’s disease. Among the symptoms of Huntington’s is “chorea”— involuntary and uncontrollable bodily movements, a symptom similar to tardive dyskinesia. The company moved the drug into a series of clinical trials to treat tardive dyskinesia, and in Phase 3 its great effectiveness led the FDA to “fast-track” it. It was approved for treatment of tardive dyskinesia in April 2017, and marketed under the name Ingrezza. Today it is a drug with some $2.3 billion in annual sales (2024), and since 2023 it has also been indicated to treat Huntington’s chorea.

Dr. Kennedy—who had no financial stake in this process, but did play an important role in validation of the science behind it—marvels about how research led “from gene to treatment.” He means that at his end, in building upon basic pharmacology studies revealing the function of the VMAT2 transporter protein in relation to the dopamine system, his group “uniquely had the required skills and well- characterized patient DNA samples in place to demonstrate the association between the VMAT2 gene variant and the clinical side effect of tardive dyskinesia.” They were also able to suggest what a potentially effective drug would have to do to correct the problem introduced by the VMAT2 gene variant. Separately, a company with a candidate drug meeting these criteria rapidly progressed to the clinic and demonstrated its efficacy.

But long before these developments, it is important to remember, was 15 years of work performed by Dr. Kennedy and colleagues treating schizophrenia patients in Toronto, some of whom had the tardive dyskinesia side effect when they took antipsychotics; and the fact that Dr. Kennedy had asked how genetics might dispose some patients to have the side effect. In short, the entire process might be said to encapsulate the power of basic clinical and molecular- genetic research to foster solutions for people who need better medicines.

Dr. Kennedy reflects: “Funding this kind of research is the essence of the BBRF concept, as it was conceived from the Foundation’s beginnings.”

The Promise of Pharmacogenetics: How It Can Help Patients

In the period following their discovery of the VMAT2 gene association with tardive dyskinesia, and the identification of a treatment validated by that finding [detailed in the accompanying story], Dr. Kennedy and collaborators were meantime working on another track to “collect the top six gene variants associated with antipsychotic-induced weight gain,” Dr. Kennedy says.

They patented that panel of genes, which included the MCR4 gene variant and the GLP-1 receptor variant [see p. 9]. The “panel” developed by Dr. Kennedy and colleagues is a small chip (like that pictured below) that harnesses genetics technology to determine, in a single low-cost lab test, how many risk variants an individual (who gives a saliva sample) carries across the multiple genetic variants that the panel targets. The risk score generated by the test will vary from one individual to the next, and this risk assessment can help a physician prescribe the optimal medication based on the higher versus lower side- effect risk scores. The panel also can be used, for instance, by pharmaceutical companies trying to develop new second- generation antipsychotics. In conducting a clinical trial for a new medication, one might want to screen for patients with genetic vulnerability to weight-gain, in order to more precisely define who will benefit most from the trial drug.

This idea of creating multi-gene “panels” that would test for specific gene variants associated with medication side- effect risks is fully amenable to patient-facing applications. Pharmacogenetics tests in theory can be used widely in different medical contexts and potentially have great value for millions of people taking medicines of many kinds for a wide variety of illnesses. The key has been to identify as many genetic variants as possible that expose those who carry them to significantly elevated side-effect risks.

Dr. Kennedy has played a pioneering role in the development of such broad-panel pharmacogenetic tests over the years. While research already described in this article was under way, he and other researchers with similar interests had been pursuing studies that led to the validation of a number of key gene variants with broad impact on the way most drugs are metabolized in the human system.

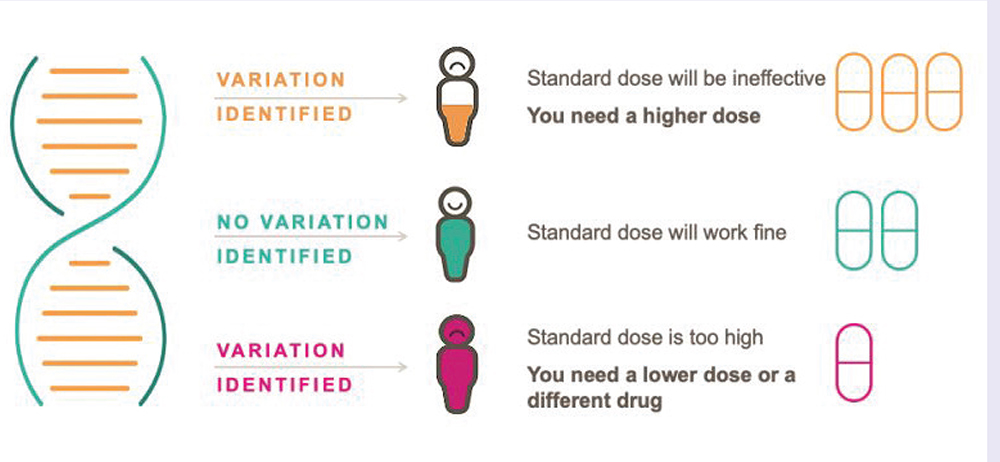

This effort, like most science, builds on basic-science findings made by earlier investigators. Beginning in the 1950s and ‘60s, research on the liver led to the discovery of enzymes that perform a wide range of essential functions, from detoxification to glucose regulation to the processing of nutrients from food. This work importantly revealed a number of liver enzymes that help process pharmaceuticals, among other molecules. They are members of an enzyme family called the cytochrome P450 family. A number of these enzymes have been found to be particularly important in metabolizing psychotropic drugs, including antipsychotics and antidepressants. Each of the key enzymes—called CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, and CYP3A4—is encoded by a gene of the same name. Variations in the DNA “spelling-out” these genes are present in many of us. About three-quarters of the population will have at least one non-normal variant across these five genes, according to Dr. Kennedy. Having one or another of them, or several of them, can mean the difference between being someone who rapidly or slowly metabolizes medicines, relative to the average person. One’s “metabolizer status” can be used to guide dosing strategies for specific medications in which these enzymes are implicated.

Other pharmacogenetic discoveries have identified gene variations affecting the way medications interact with the body, impacting the effect of specific drugs. As Dr. Kennedy and co-authors note in a 2025 review paper in Psychiatric Clinics of North America, pooled results from 13 clinical trials showed that those receiving pharmacogenetics- guided antidepressant treatment were 41% more likely to achieve symptom remission relative to patients who received treatment as usual. Further: “A recent study that included patients with schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorder showed that pharmacogenetics-guided treatment in psychiatry led to 34.1% fewer adverse drug reactions, 41.2% fewer hospitalizations, 40.5% fewer readmissions to hospital, and shorter duration of initial hospitalizations, compared to patients receiving treatment as usual.”

At this point, about 35 drugs including antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants have pharmacogenetics- based guidelines for prescription, developed by expert groups such as the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium. In some cases, the guidelines are mentioned in drug labeling by regulatory authorities including the FDA and Health Canada. According to Dr. Kennedy and colleagues in their 2025 review paper, 63% of these 35 drugs have guidelines related to gene variants for enzymes CYP2C19 or CYP2D6. People of different ethnic heritage will sometimes have different vulnerabilities to these key variants. But the variants are commonplace. For example, “depending on the population tested, 37% to 96% of people will carry at least one clinically actionable CYP2C19 genetic variant, for which a change in standard prescribing may be indicated; and 35%- 73% will carry a CYP2D6 actionable variant,” Dr. Kennedy and co-authors note.

Five genes (CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, CYP3A4) and 2 human leukocyte antigen genes (HLA-A, HLA-B) are implicated in these guidelines affecting 25 psychotropic drugs. Panels or “gene chips” have been created to enable doctors to have patients tested for these genetic variants. This capability exists today.

BARRIERS TO ADOPTION

Why, then, have the tests not yet become a standard part of patient evaluation when a medicine is going to be prescribed? Dr. Kennedy and colleagues explored “barriers to clinical adoption” in a 2021 paper in Translational Psychiatry. The answers, in brief, are that various powerful entities, perhaps most important among them payers in various healthcare systems, have claimed that the evidence for the clinical utility and economic value of the tests has not yet been sufficiently proven. Another important factor is lack of awareness on the part of some physicians as to how (or which) of the tests can help with specific classes of patients, and the medicines for which guidelines currently exist.

The latter barrier is arguably solvable via physician education. But the arguments about clinical and economic utility have been hard to counter. In the most optimistic way of thinking— Dr. Kennedy is an optimist, but also realistic about the state of the healthcare systems of Canda and the U.S.—clinical effectiveness will become harder and harder to deny as pharmacogenetics research continues to advance and be published.

Dr. Kennedy has received strong support from Larry Tanenbaum, owner of the Toronto Maple Leafs and Raptors professional sports teams. He has funded the Tanenbaum Pharmacogenetics Center at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, University of Toronto, which Dr. Kennedy heads. “The research is rapidly progressing,” Dr. Kennedy says. “But it takes a long time to do clinical trials that are large and statistically powerful, and they are very expensive.”

The research he is able to perform makes him confident that the argument for pharmacogenetics will win out in the end. After noting that the Canadian government healthcare system had raised the question of proof of effectiveness—“they didn’t feel the clinical impact was proven beyond the shadow of a doubt”—Dr. Kennedy noted that since that time, a number of additional randomized controlled trials of pharmacogenetic testing have been published. In these trials, some patients get a pharmacogenetics test and they are compared with people whose doctors dispense medication in their usual way—“treatment as usual.” The results can be eye-popping. A study Dr. Kennedy and colleagues in Toronto published in 2022, involving 370 depression patients, “showed an 88% increase in the number of patients who made it all the way to remission after receiving the test.”

This kind of information, Dr. Kennedy says, “empowers the patient to make the best informed decision about which medication to take for their psychiatric disorder.” Because results are better, “it helps the doctor-patient relationship.” Having a medicine that you can expect to respond to also encourages better adherence to medication programs. This is especially important in an illness like schizophrenia, where a significant percentage of patients discontinue antipsychotic medicines, often due to side effects. This applies to both first- and second-generation antipsychotics, and helps us better understand why, from the beginning of his career, Dr. Kennedy has been working to find genetic factors that might help deal with the phenomenon of treatment resistance. By definition, the work on pharmacogenetics is one way of dealing with the problem: some patients for whom a medicine does not work get much better results when a pharmacogenetics test shows that they have a gene that, for example, makes them excrete a drug too rapidly, or have a drug in their system for too long a time.

One other hesitation about pharmacogenetics has been addressed in recent years. Discovery of the key liver enzyme genes regulating drug metabolism was based on research mainly involving White, Euro-American populations. More recent research has made sure to include people of diverse ethnicities, from all of over the world, and has added significantly to the sensitivity and utility of the tests.

Dr. Kennedy and others are working to develop more sophisticated pharmacogenetics tests. Their most comprehensive one is built into a gene “chip” that uses a saliva sample or single drop of blood to test for a total of 60 medication-related genetic variations in 22 genes. This test, which he and colleagues hope to be able to study in a clinical trial, includes variations pertaining to eight liver enzymes affecting drug metabolism.

With respect just to these eight enzymes, “what are the chances that an individual will have none of them— no variations that result in fast or slow drug metabolism?” Dr. Kennedy asks. “If we think across all the medications a patient may take, across disorders, only 22% would not have a benefit from the test. Conversely, 78% will have at least one of these variants, and therefore will get some benefit” based on the liver enzyme variants alone.”

The tests will continue to improve, as they reflect new knowledge about individual vulnerability to factors affecting drug metabolism and effects. Factors still to be incorporated which could add considerable fine detail to an individual’s pharmacogenetic profile include polygenic risk scores, a statistical estimate of an individual’s genetic predisposition to a particular trait or illness based on the collective influence of many genetic variants; and so-called “omics” research, which adds highly detailed information from vast genomic databases about gene activation, epigenetics, protein dynamics, and RNA biology.

In the end, pharmacogenetic testing may eventually prevail because it makes good sense. “When you think about these liver enzyme genes, the case is pretty simple” Dr. Kennedy says. “They either increase the breakdown of a drug, which makes its level low in the bloodstream, which causes lack of response; or it blocks the breakdown of the drug which causes the drug to accumulate in the bloodstream, causing all kinds of side effects and toxicity.”

“It’s just unquestionably a good idea for patients, but also for doctors, using their powerful prescription pad to order a foreign chemical to go into a patient’s body. It’s dangerous if the doctor does not know whether this patient is among the subgroup who cannot break the drug down. So, the drug accumulates to very high levels and becomes toxic and has side effects. Why would a doctor not want to know that?”

Click here to read the Brain & Behavior Magazine's January 2026 issue