A Precision-Health Approach to Bipolar Disorder

By Sarah H. Sperry, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry

The University of Michigan

2022 BBRF Young Investigator

I’d like to share with you findings from my BBRF Young Investigator Award project that will hopefully challenge the way you think about bipolar disorder. If you’re living with bipolar disorder or have a loved one with the disorder, what I say here will suggest the importance of engaging in ongoing mood monitoring. The objective and hope is that such monitoring can help us develop new strategies to treat patients more effectively, to help them better function in the world and live productive lives.

For those who don’t know, bipolar disorder is one of the top 10 leading causes of disability worldwide. Despite this, progress in terms of diagnosis and treatment has been slow. I want to suggest why this might be—what we might be missing and how we might be able to move forward to catalyze change in the field.

Let me briefly review our current diagnostic criteria so that we’re all on the same page. Bipolar disorder is comprised of mood episodes, either manic, hypomanic, depressive, or mixed episodes. I’ll briefly review what each is.

Manic episodes involve feelings of elation, euphoria, and/or agitation and irritability; increased energy and a reduced need for sleep; feeling grandiose, or invincible, or superior; talking more and faster than normal; having racing thoughts; being hyper-focused on an activity or goal; pacing or feeling really restless and fidgety; being impulsive or reckless. And for some, experiencing delusions and hallucinations. For something to be categorized as a manic episode, these symptoms have to last at least one week (or shorter If they require hospitalization). Critically, they cause significant impairment in one’s health, work, and social life.

Hypomanic episodes are similar to manic episodes, but differ in intensity and duration. They involve the same set of symptoms, but in hypomania, the symptoms only have to last 4 days. Unlike in mania, they tend not to cause clinically significant impairment. But they do involve a recognizable and observable change in somebody’s affect and behavior. This is often apparent to family and friends.

People with bipolar disorder also experience depressive episodes. These can include prolonged sad and low mood, loss of energy, loss of interest in pleasurable activities, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, withdrawal from social activities and family, changes in appetite and weight, difficulty concentrating and making decisions, sleep changes such as insomnia or hypersomnia, and thoughts of death or suicide. For diagnostic purposes, these symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks and cause clinically significant impairment.

Finally, people with bipolar disorder sometimes experience mixed episodes, in which they have symptoms of mania or hypomania and depression at the same time.

The type of episode one experiences determines which bipolar diagnosis they receive. We have four primary possible diagnoses in our current diagnostic system, based on the DSM-V manual. These are bipolar I disorder; bipolar II disorder; other or unspecified bipolar disorder (previously known as bipolar NOS, “not otherwise specified”), and cyclothymic disorder. Individuals with bipolar I disorder must have a history of manic episodes. It’s not required that they have experienced depressive episodes. However, the majority with this diagnosis do experience depression in addition to mania.

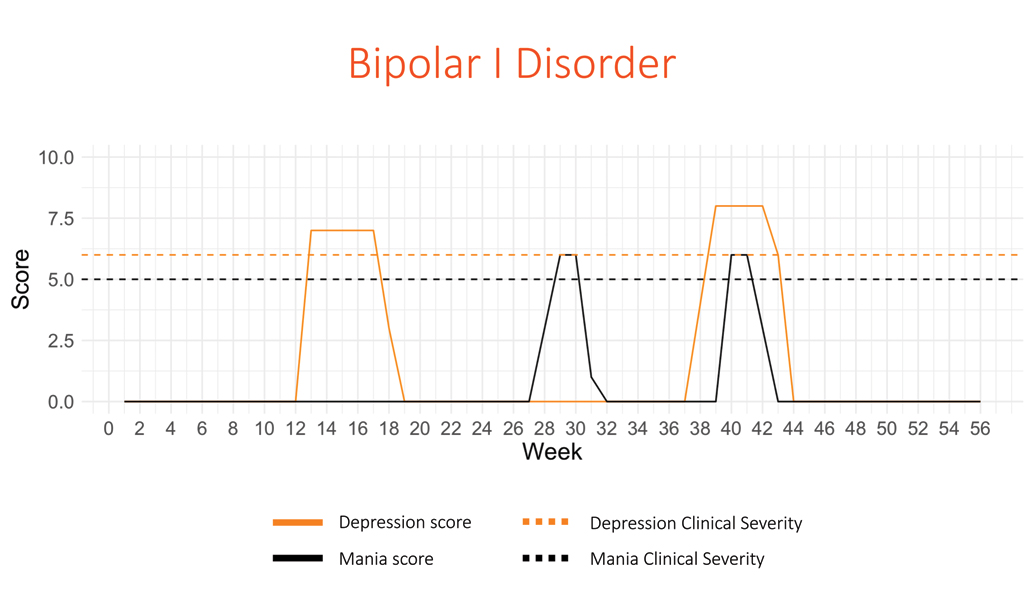

Let’s take a look at what bipolar I looks like in graphic form. This is a hypothetical classic case:

The bottom axis of the graph measures time—here, a 56-week period. The other axis shows the intensity of the symptom score this patient had during these weeks. The horizontal orange dashed line is the threshold for a depressive episode; the horizontal black dotted line is the threshold for a manic episode. Anything above these lines (in this and subsequent graphs) means the patient is having an “episode.”

This graph tells this story: over the past 56 weeks, this individual has had one pronounced depressive episode, one pronounced manic episode, and one mixed episode (experiencing symptoms of both mania and depression). Please notice that between episodes, this person has no mood disturbances—their symptom scores are all the way down to zero. This is important because extant research and clinical theorizing often emphasizes that in bipolar disorder, there is a return to normal or what we call “euthymia” in between depressive or manic/hypomanic episodes.

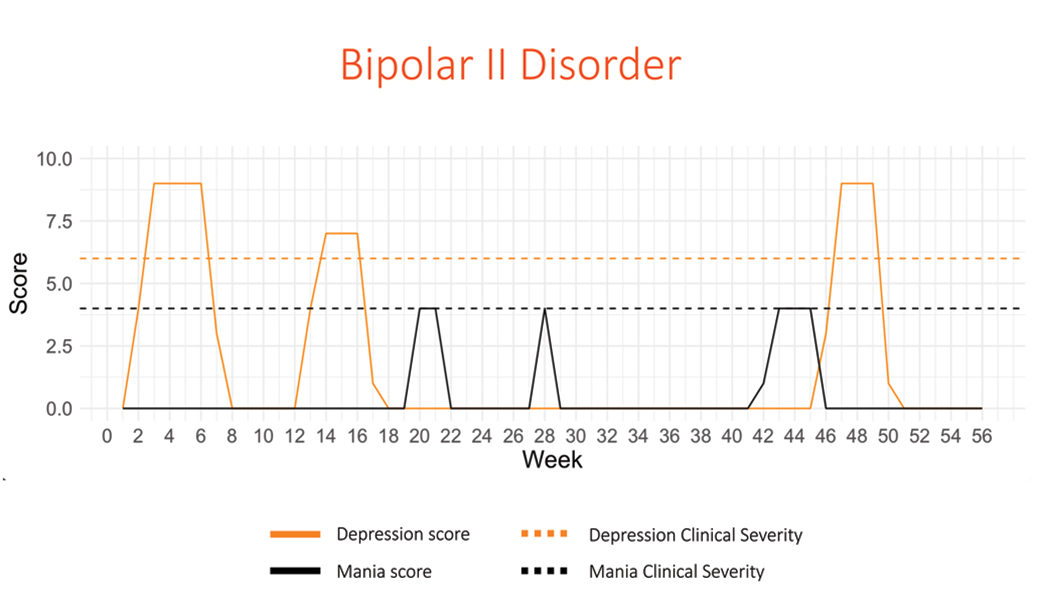

Now consider this hypothetical individual with bipolar II disorder.

Individuals with bipolar II disorder by definition have to have at least one hypomanic episode and also experience depressive episodes. This chart is set up the same as the last, but the black dashed line is lower. This represents the lower intensity of hypomanic symptoms compared to manic symptoms. What we see in this chart is that the individual has three prominent depressive episodes and three hypomanic episodes over a 56-week period. One of the hypomanic episodes (the last one) partly overlaps in time with the third depressive episode. Here again, you see that when the individual is not experiencing either depressive of hypomanic episodes, symptoms go down to zero and the individual is “euthymic."

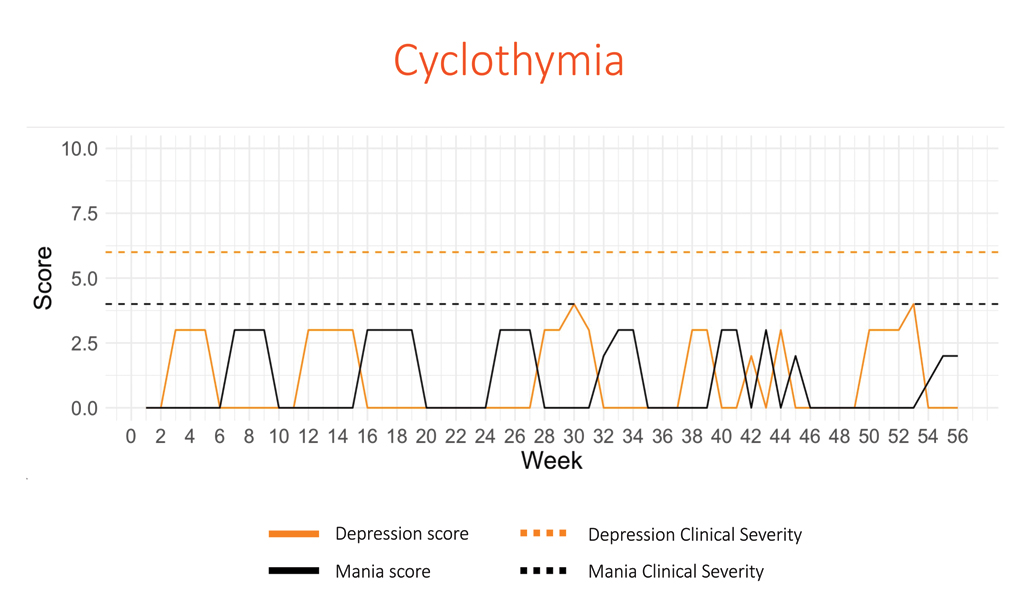

My third chart shows what a person with cyclothymia looks like, according to the official definition.

Remember, cyclothymia is when an individual has symptoms of both hypomania and depression that do not rise above the threshold for an official episode, either in intensity of symptoms or duration. But these “subthreshold” symptoms must be present for a significant amount of time, cumulatively. So, you’ll see this person experiences a lot of variability in mood, a lot of vacillation between symptoms, and less time overall spent in “euthymia,” without mood disturbances.

My point in showing you these charts is that they map onto our diagnostic criteria very nicely. But my message to you is that things do not look this clean when we’re looking at the majority of actual patients and their moods over time.

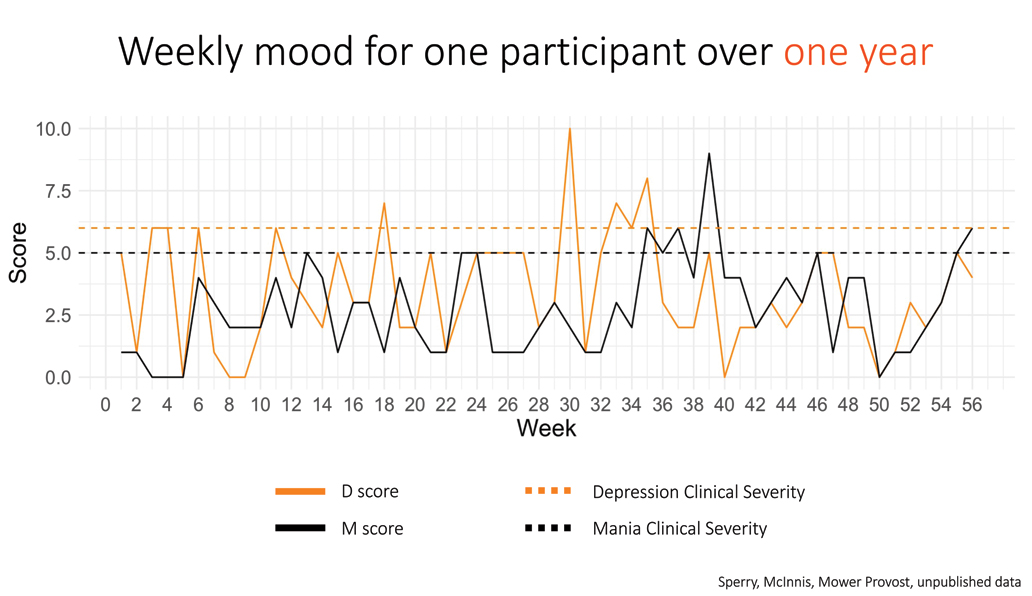

The charts I will now show you are based on data my colleagues and I gathered in a study we called PRIORI, conducted at the University of Michigan. We had 18 individuals with bipolar I or bipolar II disorder complete weekly ratings of depression and mania symptoms (or their absence) over 12 months. They did so on an application on their smartphone developed by our group at Michigan. The questionnaire includes six items that result in a depression score or D-score, and mania score or M-score. The app is very easy to use and can be filled out in less than a minute, which makes it more likely participants in our study will actually use it every day.

The image above is a chart of real-world data for one of our participants who completed the full 12-month study and a few weeks extra, 56 weeks in all. One thing you can see is that there were very rarely periods of time when this person’s mood symptoms were zero, or “euthymic.” Rather, the person vacillated between symptoms much more like the theoretical cyclothymic individual I showed you. But this person does have times where their symptoms spiked, and they had distinct clinically significant episodes. You’ll also note that this person often had some level of depressive and manic symptoms at the same time. What you don’t see is a clear-cut differentiation between depression and mania.

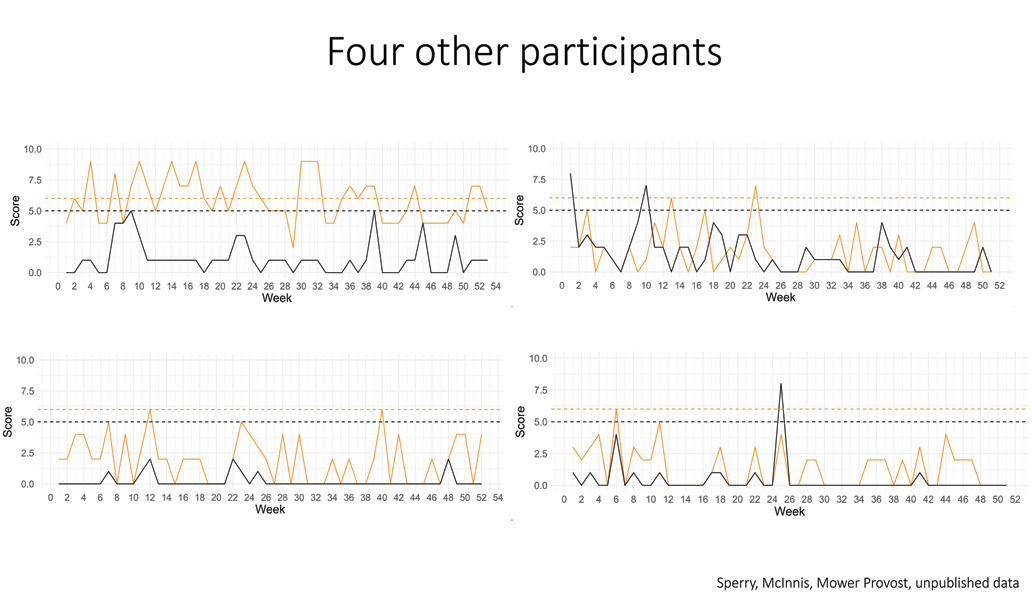

Here are four other real-world participants who recorded their moods over 56 weeks on our app.

You will notice some individual differences in these patterns. For example, the individuals on the bottom spend more time at zero in terms of manic symptoms (black lines), so they look a bit closer to our textbook-definition examples of bipolar I and II disorders that I showed you earlier. But they have a lot more variability and depressive symptoms (orange lines). You’ll note that the individual on the top left experiences frequent but small shifts in manic symptoms, whereas their depression is consistently high and variable.

Over the 8 years of my initial research, data I had generated on people with bipolar diagnoses suggested that individuals differ significantly in their presentation and course. This “heterogeneity” within bipolar disorder is complex and a challenge for research and treatment.

I also want to emphasize that mood instability is present throughout much of the course of bipolar illness, even outside the context of distinct mood episodes. One implication is: the conceptual theory of “euthymia” in between mood episodes doesn’t seem to be typical of many people with bipolar disorder if you carefully chart the pattern of their moods over time. The question I started to ask myself was: can we stratify individuals based on these patterns of affective instability? This, as opposed to stratifying them based on the type of episodes they experience (“manic” or “depressed”) or the diagnosis they come to us with (bipolar I, II, or cyclothymic).

I had the thought: If I took those five time-series charts from the PRIORI study I showed you, I could use models to describe how these individuals differ from each other—I mean, in the actual dynamics of their depression and mania. Thankfully, BBRF liked this idea, as did Thomas and Nancy Coles, who sponsored the Young Investigator Award that supported my project to attempt this non-traditional stratification of bipolar patients.

The aim has been to model and thereby be able to predict mood dynamics. I think of this as a “precision health” approach to bipolar disorder. In this project, which started mid-2022, I proposed to look at a unique cohort of individuals with bipolar disorder over a period of time, the Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder (PLS-BD) at the University of Michigan. This unique cohort includes about 1,400 individuals who have been followed from anywhere from zero to 16 years. Although we took a snapshot of the existing data in 2022, the PLS-BD is an ongoing study, recruiting new participants, and following participants already enrolled.

Of the 1,400, about nearly 70% have a bipolar spectrum disorder. About 20% have no psychiatric diagnosis and are considered healthy comparison subjects. Others had non- bipolar psychiatric diagnoses. I proposed to focus on those individuals with a bipolar I, II, or NOS diagnosis who had at least 5 years of data we could model. This allowed me to have a sample size of 731 individuals. About 70% have bipolar I, about 20% have bipolar II and just shy of 10% have a bipolar NOS diagnosis.

When people enrolled in the study, they went through a baseline assessment that included an extensive diagnostic interview. They gave biological samples and filled out many questionnaires, and did interviews about trauma history, personality, temperament, family history, and neurocognitive functioning. After enrollment, every 2 months they completed self-report measures of mood and functioning. Every 6 months, they completed self-report measures on substance use and sleep quality. Each year, they underwent a clinical assessment where we rated their manic and depressive symptoms. They also completed some additional measures on family dynamics over time, and did a medications update. At year 2 or every 2 years, they underwent a comprehensive interview that updated their medical and psychiatric diagnostic and treatment history, and also any new history of suicidality. And every 5 years, they had a reassessment of their neurocognitive functioning and personality.

It’s exciting that for many of these individuals, we were able to integrate this data with their electronic health record data, allowing us to really garner a lot of deep information that can be used to try to predict treatment response, trajectories of change, and so on.

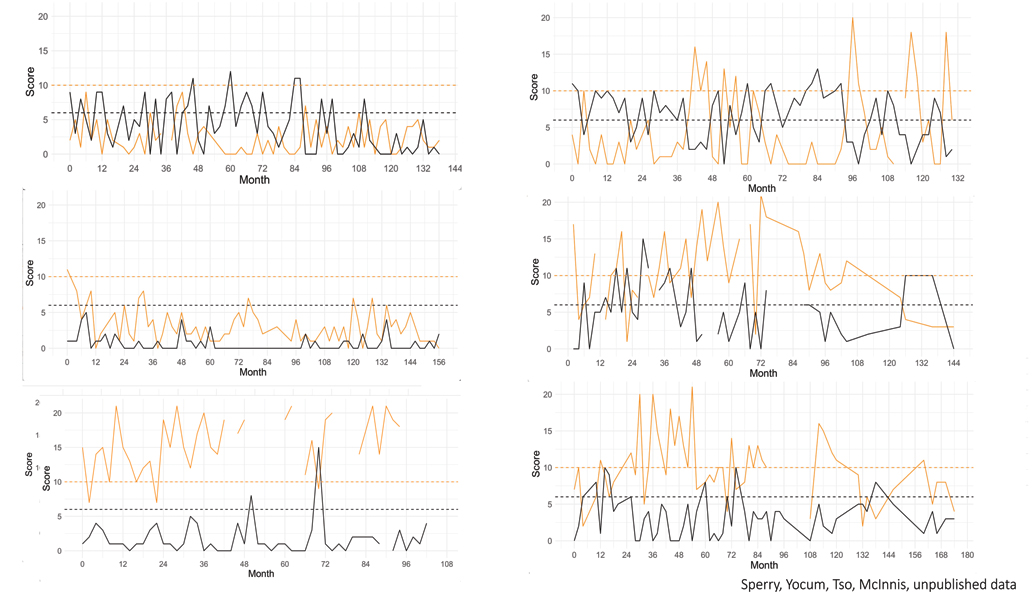

Here are mood charts of six individuals who have been in the PLS-BD cohort for over 10 years. As you can see at a glance, there are lots of different patterns.

What do we do with all of this data? First, we can calculate the “mean” or middle point of each person’s depression and mania over time. We think about these “means” as the average level of depression or mania that somebody experiences. Another way of putting it is that they are somebody’s “home base,” emotionally. It’s the place that their body inherently goes back to most of the time. Next, we can look at what’s called variability. This is how much a person deviates away from their home base. At any point in time you can ask: how intense or less intense are the symptoms at this point compared to what they look like on average? From this information we can compute, statistically, to what extent mood at one point in time predicts mood at the next point in time.

You can think about this as a way of showing how long it takes an individual to “return to baseline” when they do have a mood shift. It can also show, among other things, how mood may be consistent over periods of time.

For each of the 731 individuals with bipolar disorder in my data, I can put their time series of depression and mania data through my model (which is more complex than is necessary to explain here). The next question is: based on the data, can I group people, or stratify people, based on the temporal dynamics of their mood?

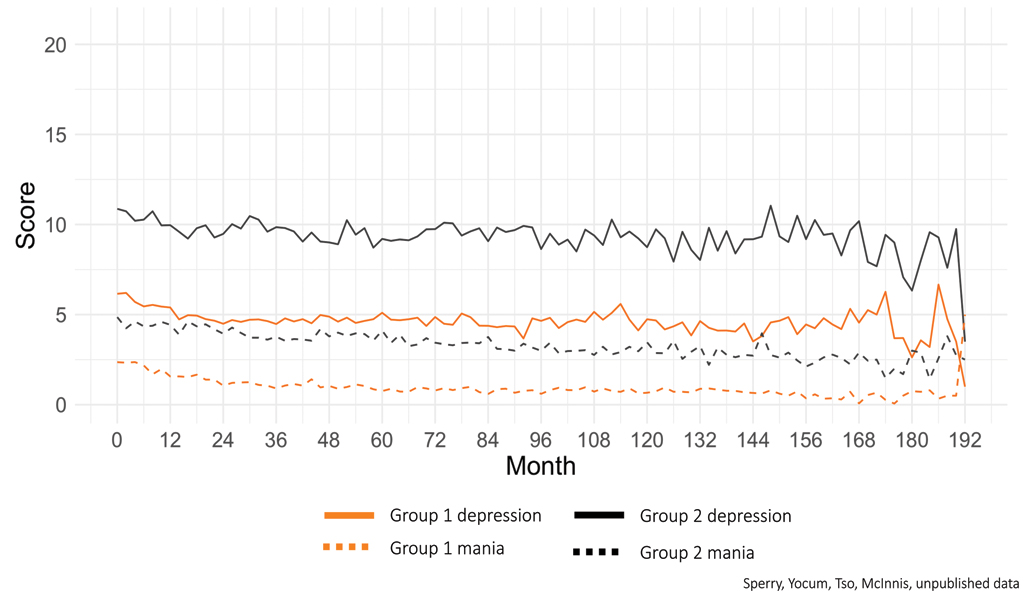

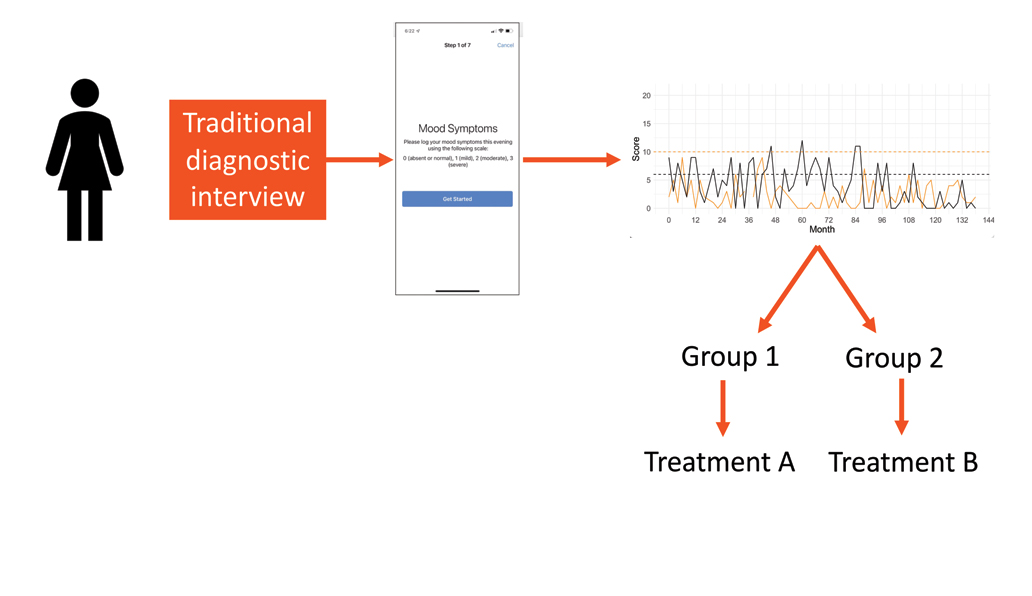

In our 731 individuals with bipolar disorder, we found two meaningful groups. I’m just going to call them Group 1 and Group 2 for simplicity’s sake. 253 of our individuals fell into Group 1 and 478 fell into Group 2. I took everybody’s data and I found the average level of depression and mania for each group at each point in time.

The solid black line represents depression for everybody in Group 2, over time. The black dashed line represents Group 2’s mania over time. The solid orange line represents Group 1’s depression, and the orange dashed line represents Group 1’s mania. Right off the bat, you can see that Group 2 tends to have higher average levels of depression and mania. You can also see that Group 2 seems to have more variability in their scores.

After lots of additional analysis, we were able to conclude that Group 2 are individuals with bipolar disorder whose emotional course is characterized by a high intensity of symptoms, but more importantly to me, high variability in these symptoms.

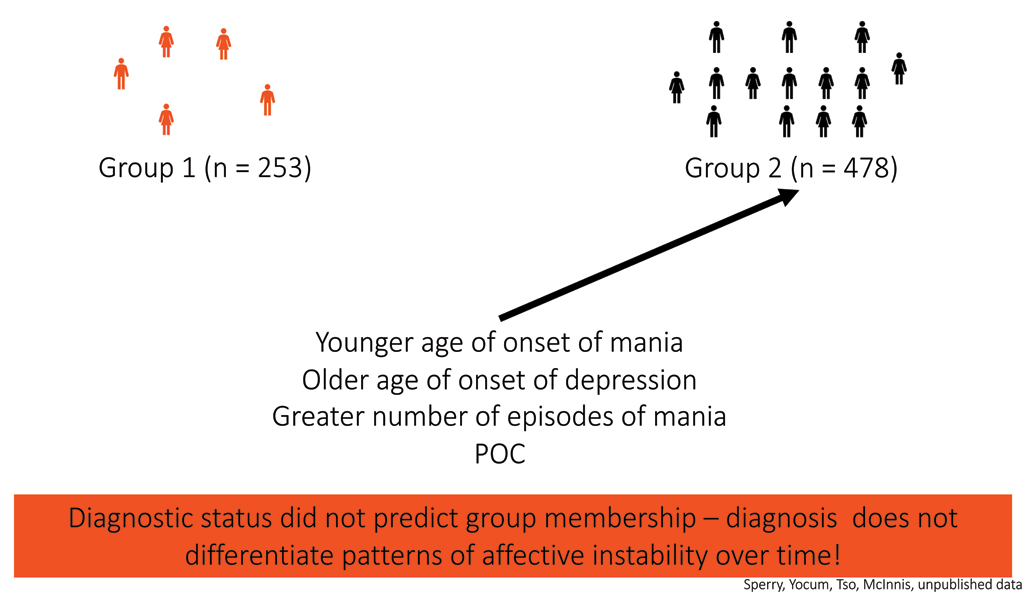

The next question is: are there predictors that help us know who is likely to be classified as Group 1 or Group 2? There are many diagnostic and demographic variables that might help us understand some differences about these two groups.

What we found is that these four variables predicted group membership. Those with a younger age of onset of mania or hypomania, older age of onset of depression, and a greater number of episodes of mania, were more likely to be classified as Group 2. The 4th variable is that Black, Indigenous, Hispanic, Asian and other people of color people of color were also more likely to be in Group 2.

What I want to stress here is that the standard “diagnostic status” (i.e., bipolar I or II, etc.) did not predict group membership. And if you remember, traditional diagnostic criteria are supposed to tell us something about the course and episodic nature of the illness. But here, the data suggests that DSM-V diagnosis alone doesn’t differentiate somebody’s level of affective instability.

The next important question I asked is: does group membership predict outcomes? Does being in Group 1 or 2 predict a person’s mental and physical health functioning? We found that people in Group 2 have lower mental and physical health functioning over the course of their illness, by a significant amount that’s very noticeable.

To recap all the big lessons we’ve learned so far:

1) Individuals with bipolar disorder experience considerable instability in mood between mood episodes—the typical pattern does not seem to be that you return to “euthymia,” or no mood symptoms, after having either a manic or depressive episode.

2) Individuals with bipolar disorder can be stratified by their level of mood instability.

3) Demographics and age of onset differentially predict levels of mood instability.

4) Levels of mood instability predict how well or poorly, in relative terms, that you will function both mentally and physically.

In our ongoing work, we hope to refine our models incorporating larger amounts of data, confirm the number of mood instability “classes” we identify, and look at other factors that might enable us to predict which group that someone with bipolar disorder will fall into, as well as how group membership may predict outcomes. We’re going to be looking at whether sleep and circadian rhythms, trauma history, personality and temperament, family history, and health comorbidities, predict group membership. Regarding outcomes, we’ll look at things like ER visits and hospitalizations, substance use, neurocognitive functioning, suicide risk, quality of life, medication history, and therapy response.

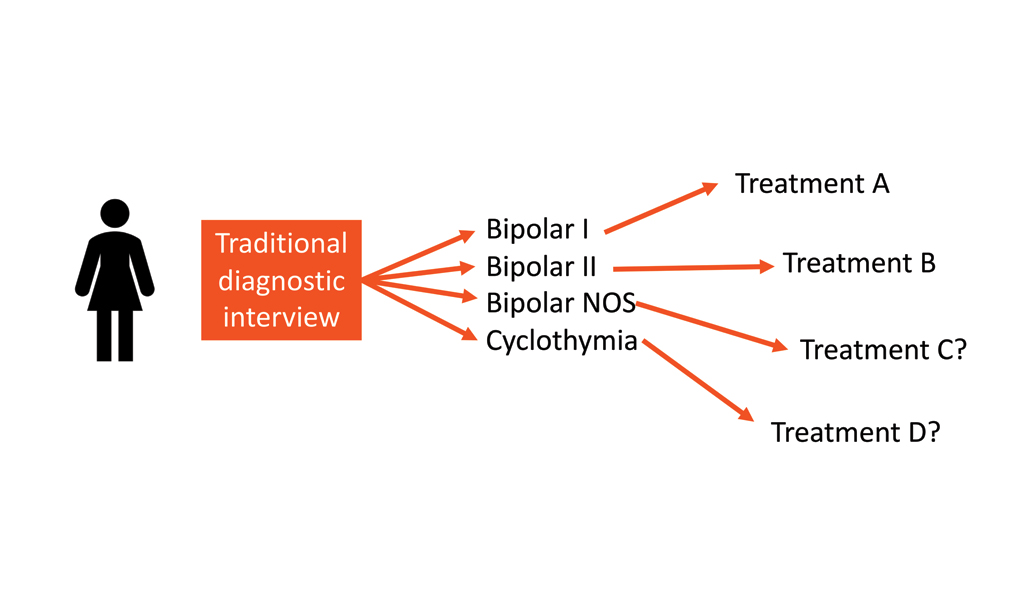

In the system as it stands today (see graphic immediately below), we choose treatments for patients based on the diagnosis, and if treatment doesn’t work, we reevaluate, we try something else. We have second-line treatments, third-line treatments, and go from there.

What I’m proposing (see graphic below)—it could be the basis of a precision-health approach to bipolar disorder—is that when somebody comes in for a diagnostic interview, the process includes mood monitoring. What if our patients and our research participants filled out our questionnaire once a day for 14 days? That would give us a time series for them in terms of their depression and mania. We are currently exploring what the minimum amount of time is that would need to be measured to calculate a meaningful metric of mood instability.

This might enable us to classify them, and determine whether they’re more like those with the illness in Group 1 who have low variability and a more episodic course, or those in Group 2 who have chronic variability.

We might then think of developing treatments for “mood or affective instability,” rather than based on whether someone is diagnosed with, say, bipolar I or II. This is my opinion, based on my program of research to date, and I know that it’s probably controversial. But the data shows me that classifying people by mood instability is potentially more meaningful than by diagnosis alone. What if we had treatments that mapped onto the actual pattern of a patient’s symptoms rather than on their diagnosis? That’s my dream.

Although my research program is still in its early days, what I’ve been able to do so far, with BBRF’s help, enables me to suggest this takeaway: affective instability in bipolar disorder is something we must pay more attention to. I would like to propose that reducing the reactivity and variability of mood in our patients could be an important way of judging the outcomes of the treatments we provide. We may find that reducing the variability of depressive or manic episodes could be an important way to improve functioning in people with bipolar disorder.

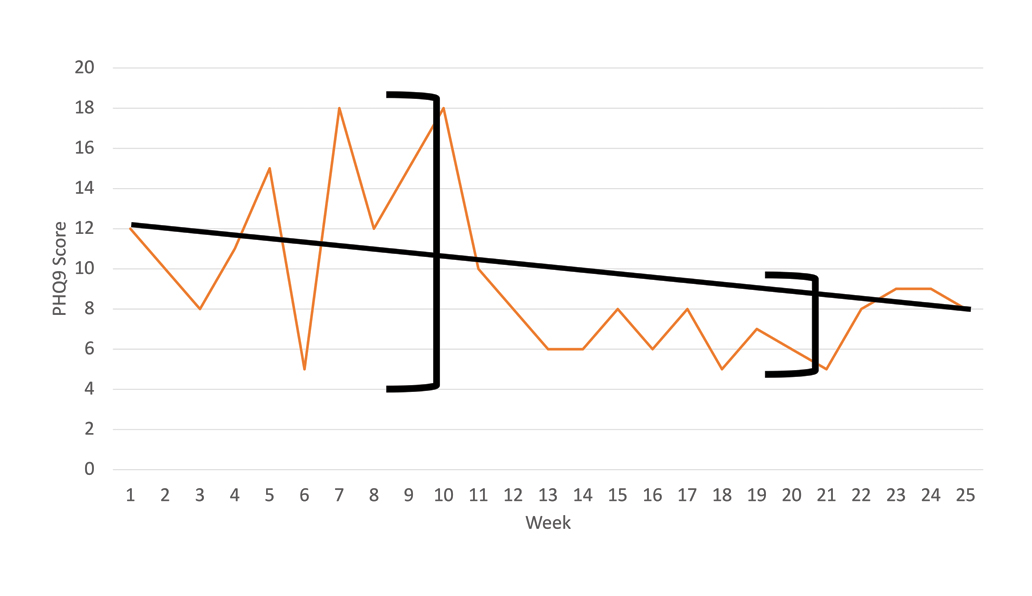

This final graphic shows what that might look like.

The orange line registers variations in the intensity of a hypothetical patient’s depressive mood over a period of 25 weeks. The change from the initial reading of symptoms at week 1 and the final level at week 25 is significant but not that large (the slope of the solid black line connecting levels at week 1 and week 25 is shallow). Further, the week-1 vs week-25 levels do not tell the story of what the patient experienced between those time points. Compare the range of variability in symptom intensity through week 9, which is large (black bracket “A”), with the much smaller range at, say, week 20 (black bracket “B”). It’s possible that such a patient, over the latter half of the treatment period, would have been better able to function because his or her symptoms tended to vary less, and at levels much lower than were experienced during the first 9 weeks of the treatment course. We might call this a success.

Click here to read the Brain & Behavior Magazine's February 2025 issue