Chronic Stress Drives Immune Cells to Remodel Neural Circuits, Possibly Promoting Anxiety and Depression

Chronic Stress Drives Immune Cells to Remodel Neural Circuits, Possibly Promoting Anxiety and Depression

Chronic stress alters neural circuits in the brain, increasing the risk of depression and anxiety. According to animal studies reported in the January issue of the journal Biological Psychiatry, some of these changes are mediated by the immune cells that reside in the brain.

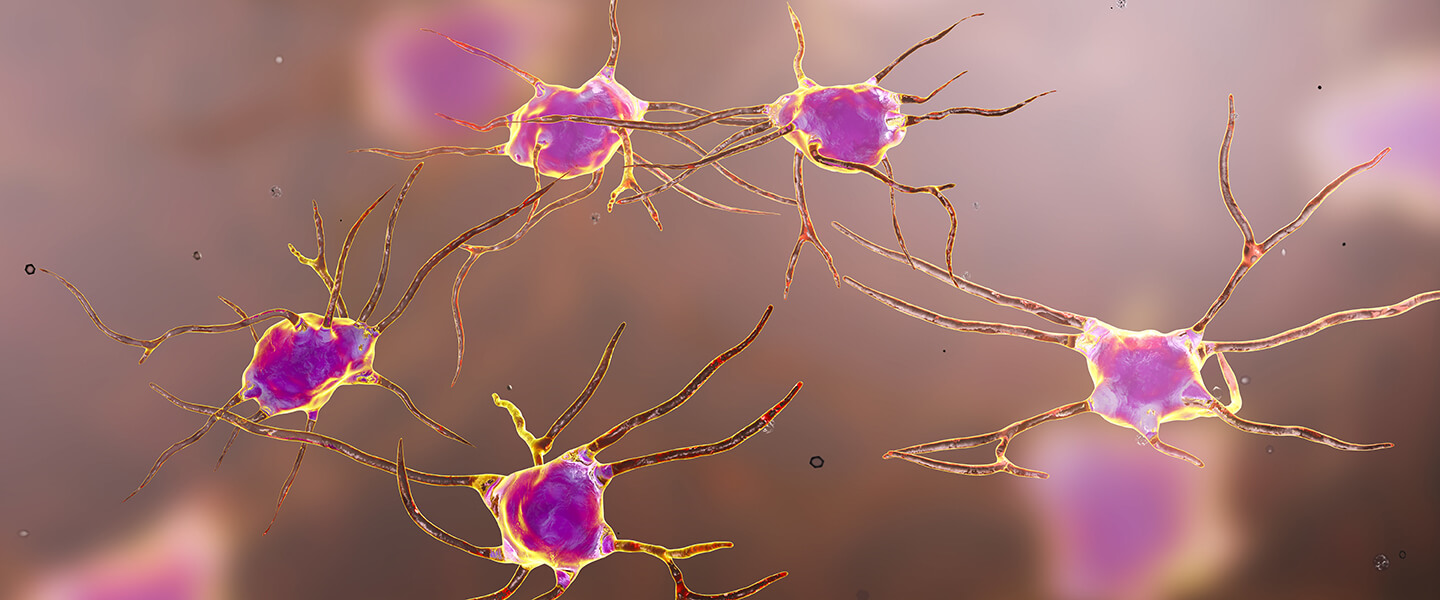

The brain’s resident immune cells are called microglia. They are responsible for fending off infections, but this is not their only role. They also help build and remodel neural circuits. Such activity is constantly going on in the brain. In the current study, researchers led by Ronald S. Duman, Ph.D., a 2005 Distinguished Investigator at Yale University, investigated what happens to the brain’s microglia under conditions of chronic stress. Dr. Duman was also a 1997 Independent Investigator, 1989 Young Investigator, and the 2002 Nola Maddox Falcone Prizewinner. Eric S. Wohleb, Ph.D., a 2016 Young Investigator, is first-author of the paper and initiated these studies as a postdoctoral scholar in the laboratory of Dr. Duman. Dr. Wohleb is currently at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

They conducted their studies in mice, intermittently exposing the animals to stressful conditions over a few weeks, then examining the impact on their brains. As expected, the treatment provoked anxiety and depression-like behaviors in the mice.

The team’s experiments showed that under conditions of stress, neurons in the brain’s prefrontal cortex—a region involved in complex functions such as decision making and social behavior—produce a signal that triggers microglia to begin remodeling neural circuits. As a result of these functional changes in microglia, neurons in the prefrontal cortex lose a portion of their synaptic connections. This is important because limited connectivity in the prefrontal cortex has been linked to major depression in clinical studies.

The research team found that when they prevented neurons from producing their microglia-stimulating signal, mice exposed to chronic stress did not develop signs of anxiety or depression. The finding suggests that interrupting stress-induced signaling between neurons and microglia might be a way to treat anxiety and depression in patients.