How COVID Infection May Damage the Brain and Affect Mental Illness Symptoms & Mortality

How COVID Infection May Damage the Brain and Affect Mental Illness Symptoms & Mortality

SCIENCE IN PROGRESS – from Brain & Behavior Magazine, September 2021 issue

Over the last year, research performed by BBRF grantees and Scientific Council members has helped to build a growing body of evidence linking COVID-19 infections with damage to the brain.

This research suggests how, in some cases, the virus may be exacerbating existing brain and behavior disorders, and in other cases may be giving rise to symptoms that were not present prior to a COVID infection. The new research also suggests that some people with psychiatric disorders are at significantly greater risk for contracting the virus, and for having worse outcomes relative to COVID patients who don’t have a psychiatric diagnosis. Finally, recent research on COVID’s impacts indicates how racial and socioeconomic factors can exacerbate risk and pose obstacles to care for those who are underserved by the healthcare system.

In a striking example of how support for basic research can contribute to urgently needed practical knowledge in moments of crisis, a team of investigators at Columbia University in March 2021 published a report in the journal JAMA Psychiatry explaining the potential causes of a wide range of neuropsychiatric symptoms seen in some patients infected with the COVID-19 virus.

The report’s lead author, Maura Boldrini, M.D., a neuropathologist and psychiatrist, is a 2014 BBRF Independent Investigator and 2006 and 2003 Young Investigator. She was joined by Peter Carroll, M.D., Ph.D., a pathologist and cell biologist also at Columbia, and Robyn Klein, M.D., Ph.D., an expert in pathology, immunology, and neuroscience at Washington University St. Louis.

In addition to anosmia—a loss of the sense of smell commonly reported by COVID-19 patients and therefore linked to the brain’s olfactory processing system— the researchers noted a range of other reported neuropsychiatric symptoms in COVID patients. These include cognitive and attention deficits (“brain fog”), newonset anxiety, depression, psychosis, seizures, and suicidal behavior.

Symptoms such as these have been present in COVID patients before, during, and after respiratory symptoms caused by the infection, the researchers noted, and importantly they appear to be “unrelated to respiratory insufficiency.” Rather, they said, these brain and behavior symptoms “suggest independent brain damage” attributable to COVID-19 infection.

Research on COVID-19’s impact on the brain is preliminary. Patient follow-ups conducted in Germany and the UK found post-COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms in 20% to 70% of patients—a very wide range reflecting their still uncertain prevalence. The symptoms were seen in young adults as well as older adults, and in some instances lasted months after the resolution of COVID’s respiratory symptoms. This evidence suggested to Dr. Boldrini and colleagues that “brain involvement” due to COVID-19 infection persists in many cases.

In search of biological processes which may be interrupted by COVID-19, the researchers began with the question of how the virus enters the body. This is thought frequently to occur at cellular receptors (called ACE2 receptors) that stud the surface of cells found in cells of the lungs and arteries, but also in the heart, kidneys, and intestines.

The “spike proteins” that project from the surface of COVID- 19 viral particles latch onto ACE2 receptors, enabling the virus a point of entry into such cells. Once inside, the virus “hijacks” the cells’ genetic machinery in order to produce thousands of new copies of itself, which are then released into the space between cells, spreading the infection.

DAMAGE FROM INFLAMMATION

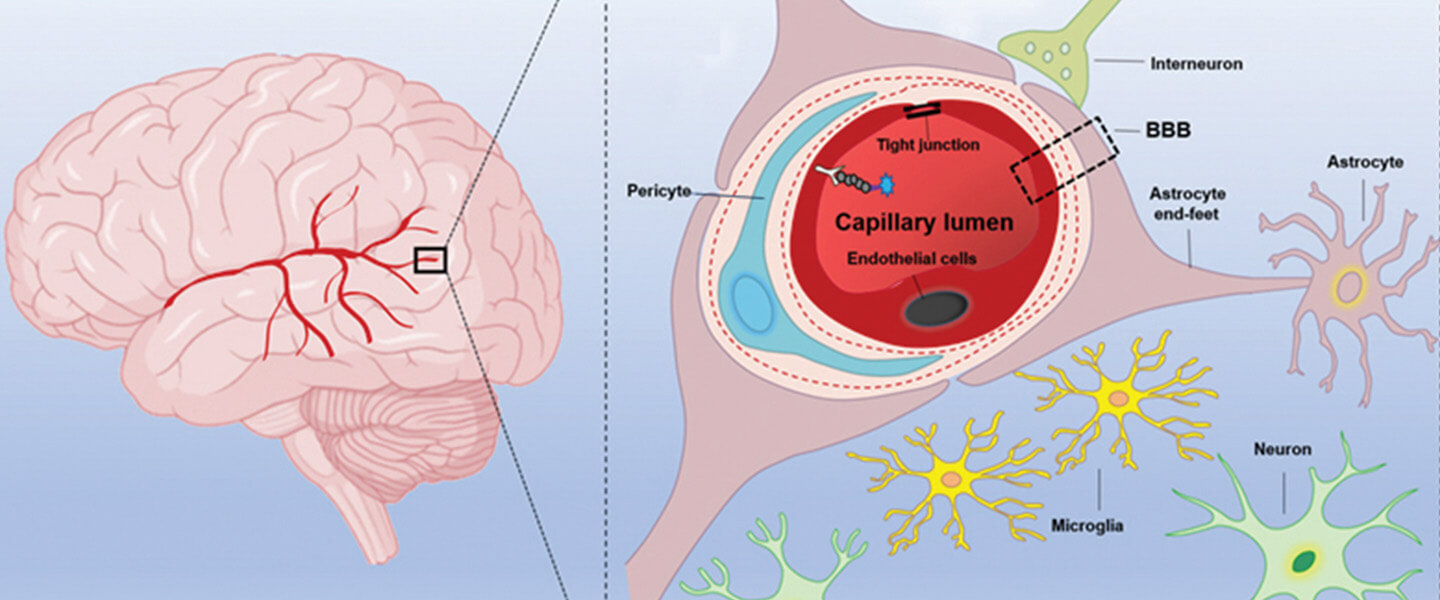

In various organs of the body, the virus can enter endothelial cells which line the interior of vessels and arteries, and damage them. This in turn can cause inflammation. Inflammation has a wide range of impacts in the body, varying according to where it occurs. If it occurs in blood vessels inside the brain, Dr. Boldrini and colleagues noted, it can cause the formation of blood clots (thrombi), and lead to brain damage.

When inflammation becomes systemic in the body, it can have many effects. Among these are decreased production of monoamines and trophic factors—brain proteins involved in neurotransmission and maintenance of neuronal growth.

Inflammation also leads to the activation of microglia. These are immune cells unique to the brain and spinal cord which have the crucial role of removing plaque-like build-ups in the central nervous system (CNS) as well as removing damaged or unnecessary neurons and synaptic connections.

Substantial reduction in microglia numbers has been associated with increased activity of the excitatory neurotransmitters glutamate and NMDA. Such heightened activity can sometimes result in what scientists call excitotoxicity, a kind of damage caused by overactivation of excitatory neurons and their receptors.

The researchers note that COVID-19 proteins have been found in the lining of blood vessels in the brain. While evidence is still lacking as to whether COVID-19 infects the brain directly, the researchers describe how viral particles might leak through the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a membrane that is designed to protect the brain from viruses, toxins, and other harmful factors. Another possible entry point into the brain, they note, is via the circumventricular organs, highly permeable capillaries around the brain’s fluidfilled 3rd and 4th ventricles. These capillaries lack a bloodbrain barrier.

The researchers speculate that loss of the sense of smell as well as nausea and vomiting may be related to viral invasion of brain and CNS vasculature. They further suggest that other short- and long-term neuropsychiatric symptoms “are more likely due to neuroinflammation and hypoxic injury”—a deficiency of oxygen due to interruption of blood flow in the brain.

COVID-19 infiltration of the brain stem, they add, may be involved in problems with the autonomic nervous system, which controls heart rate, respiration, and digestion, and has components that manufacture the main neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine). Damage to these components can lead to cardio-respiratory shutdown, gastrointestinal symptoms, and emotional and cognitive symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and an inability to concentrate (“brain fog”), which have affected COVID-19 patients, the team points out.

In explaining other impacts of the virus upon the brain and CNS, the researchers note that when the virus enters the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels of the brain, cells called neutrophils and macrophages are activated, and thrombin is produced. These are among the factors leading to the production of “microthrombi” within blood vessels—tiny clots. “Neuropsychiatric symptoms of COVID-19 could result from micro-strokes and neuronal damage,” they say, with the specific symptoms varying in patients according to where in the brain or spinal cord such events occur.

In a paper appearing in July in Nature Medicine, researchers at UCSD led by Joseph Gleeson, M.D., and including first author Lu Wang, Ph.D., a 2019 BBRF Young Investigator, reported another mechanism through which COVID may infect brain cells. The team created “assembloids”—stem cellgenerated research models consisting of various brain-cell types. These revealed that pericytes, support cells that wrap around the brain’s blood vessels, express ACE2 receptors. Entering pericytes via these receptors, the virus might then reproduce and subsequently infect astrocytes. Or, the team said, infected pericytes might generate inflammation in blood vessels, thus triggering damaging impacts upon the brain like those described by Dr. Boldrini and colleagues.

Pathologies induced by COVID- 19, as best as they can be deduced now, suggest to Dr. Boldrini’s team a variety of potential interventions to lessen their impact. These include: administering agents which suppress cytokines, the immune-signaling molecules involved in generating the “cytokine storm” associated with pathology in severe COVID-19 cases; administering agents such as ketamine which suppress NMDA receptors; and administering agents such as aspirin and celecoxib (Celebrex) which have an anti-inflammatory effect.

HOW PATIENTS ARE AFFECTED

At a different level of analysis, other researchers have studied whether and how people with psychiatric illnesses or heightened vulnerability to them are affected by COVID.

A team led by BBRF Scientific Council member Nora Volkow, M.D., studied the health records of over 61 million Americans aged 18 and over, 11.2 million of whom (18%) had a history of a mental disorder at some point in their life. Dr. Volkow, a scientist who has made important discoveries about the biological bases of addiction, is Director of the NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Her team focused on 15,110 people among the 61 million, who had been infected with COVID-19. About 36% of these individuals had been diagnosed with a mental disorder, and nearly 63% of this subset had been diagnosed within the prior 12 months. The study revealed that people with a lifetime history of mental disorder had increased risk of contracting COVD-19 infection, and that those diagnosed in the last year were especially at risk, not only of getting the virus but of having a bad outcome. Indeed, 8.5% of those diagnosed in the last year died due to COVID infection—a rate more than four times that in the general population. (In the U.S. as a whole at the time of this writing, over 33 million have contracted COVID and over 600,000 have died, a mortality rate of about 1.8%).

In their paper, Dr. Volkow and colleagues identify individuals with mental disorders as a “highly vulnerable population for COVID-19 infection.” They note that those with mental illness have “life circumstances that place them a higher risk for living in crowded hospitals or residences, or even in prisons,” environments in which infections can spread rapidly. Also, “people with disabling mental illnesses are likely to be socioeconomically disadvantaged,” a fact which “might force them to work and live in unsafe environments. Homelessness and unstable housing may affect their ability to quarantine Stigma may result in barriers to access to healthcare for patients infected with COVID-19, or make them reluctant to seek medical attention for fear of discrimination.”

HIGH RISKS IN SCHIZOPHRENIA

Delusions and hallucinations are among the symptoms of psychosis, a condition which occurs most often in people with schizophrenia, but also in some people with bipolar disorder and more infrequently in severely depressed individuals.

A study conducted in a major New York City hospital system found that people with schizophrenia had 2.7 times the risk of dying within 45 days if they were infected with the COVID-19 virus. Higher mortality was not seen, however, in people with depression or anxiety who contracted the virus.

The study, appearing in JAMA Psychiatry, was based on medical records complied in the spring of 2020 at the NYU Langone Medical Center. Donald C. Goff, M.D., of NYU Langone was senior member of the team. He is a 2009 and 2003 BBRF Independent Investigator. The team also included 2005 BBRF Distinguished Investigator Mark Olfson, M.D., MPH, of Columbia University.

Their study was based on electronic medical records of 26,540 patients tested for COVID within the multicenter NYU Langone health system over a several-month period. The mortality result for people with schizophrenia was second highest of any subgroup in the study, after that of elderly people. Drs. Goff, Olfson and colleagues noted that the elevated risk in schizophrenia remained significantly elevated even after statistically adjusting for various comorbidities and other risk factors associated with schizophrenia.

The particular risk COVID poses for people with schizophrenia was the subject of another study, which appeared in the European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. First author Gregory P. Strauss, Ph.D., 2018 BBRF Young Investigator, and colleagues at the University of Georgia focused on how COVID infection may have impacted patients’ “negative symptoms.”

Negative symptoms in schizophrenia include social withdrawal, blunted facial and vocal affect, decreased motivation, and the inability to seek pleasure (anhedonia). The researchers sought to determine whether social isolation, physical distancing, and other public health precautions had the effect of exacerbating patients’ negative symptoms.

They found that this was indeed the case, in a sample of 32 individuals with chronic schizophrenia who were compared with 31 healthy controls. The study also studied 25 individuals considered to be a “clinically high risk” of psychosis based on family history, genetic factors, or mild, potentially “pre-psychosis” behaviors, comparing them with a group of 30 healthy controls.

The investigators found that a wide range of negative symptoms, involving speech production, blunted affect, anhedonia, lack of volition, and social withdrawal, were worse, on average, in the schizophrenia patients while the pandemic was in progress, compared with before it began. Among the “high-risk” group, anhedonia and lack of motivation was worse during the pandemic compared with before it began.

Dr. Strauss and colleagues said their study suggests that negative symptoms “should be a critical treatment target during and after the pandemic” in people diagnosed with schizophrenia as well as in others on the schizophrenia spectrum, given the chance that they will have worsened during this time of great stress.

Written By Peter Tarr, Ph.D.

Click here to read the Brain & Behavior Magazine's September 2021 issue